Colgate at War, 1943

Colgate became directly involved in U.S. preparations for action in World War II (which was already well underway in Europe) by September 1940, when the Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) program was established under the auspices of the federal government. The Colgate Airport, emblazoned with the slogan, “Home of the Flying Red Raiders,” opened a new hangar and an expanded landing strip 5 miles north of campus, on Route 20 in Bouckville.

(In hindsight, portents of World War II had materialized on campus as early as the 1930s, when the university hosted lectures by both visitors and members of the faculty, who spoke candidly — and often controversially — about Hitler’s reign in Europe.)

The initial class of 30 students in the CPT program received ground instruction and flight training using three Piper Cubs. Although university officials initially seemed hesitant to link the program with any conditional military service, a letter from President Cutten to the Board of Trustees noted it was to be “assumed that this training might eventually be of assistance in national defense.”1 Indeed, flight training and aeronautics would be central to the university’s military training programs once the war began.

The university’s wartime activities began to increase by September of 1942 (just under a year after the United States officially entered the war), when Colgate installed its new president, Everett Needham Case. In his inaugural address, Case noted the direct and vital impact of the war on the Colgate community: three-quarters of men who had graduated the previous spring were now training and fighting in the armed forces. Soberly, he told the crowd that eight of these Colgate men had already died.

Has Socrates, like yesterday’s motor car, been rendered obsolete by high octane gas?”

President Everett N. Case Inaugural address, September 24, 1942

Case’s inaugural speech — the first of many he would give concerning the war — would prove to be more than grim statistics. He encouraged critical analysis of the role of liberal arts colleges in creating students who would be not only prepared to win wars through contributions to science and technology, but also informed, educated citizens for a peaceful, postwar world. In order to avoid yet another “savage and ruthless” war, he said, colleges must train students to be wise global citizens who could “work effectively with these millions of human beings whose backgrounds and ways of living are so different from ours.” And while he surely touted the role of education in society’s gains in science, technology, and industry, he warned against the “spiritual deflation” and “social waste” that might arise from an education not balanced with studies also in the humanities and social sciences.2

While his inaugural speech extolled philosophical visions of a postwar future, President Case was efficient and practical in his management of the campus during wartime. He recognized that traditional student enrollment — and thus, the university’s very viability — was in peril because of military enlistments and a probable draft. Indeed, the young high school graduates who were the lifeblood of the all-male college were members of the same demographic required to fight in this world war. Case’s first months on the job no doubt consisted of calculations and evaluations of how Colgate might survive these realities.

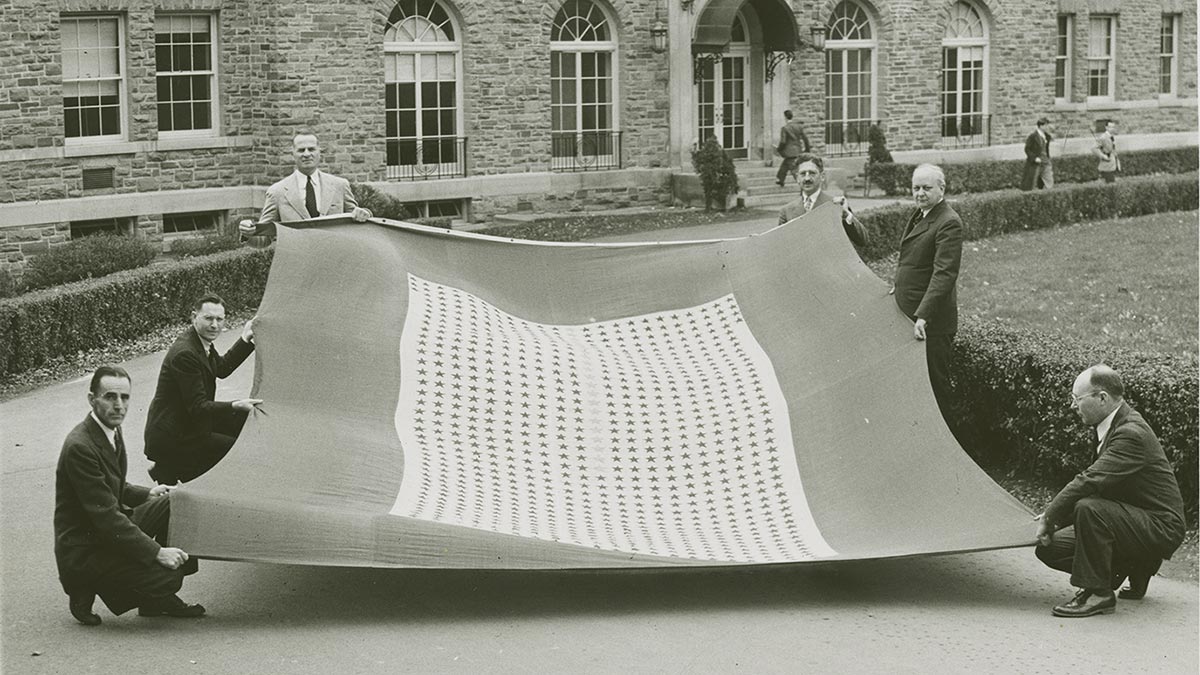

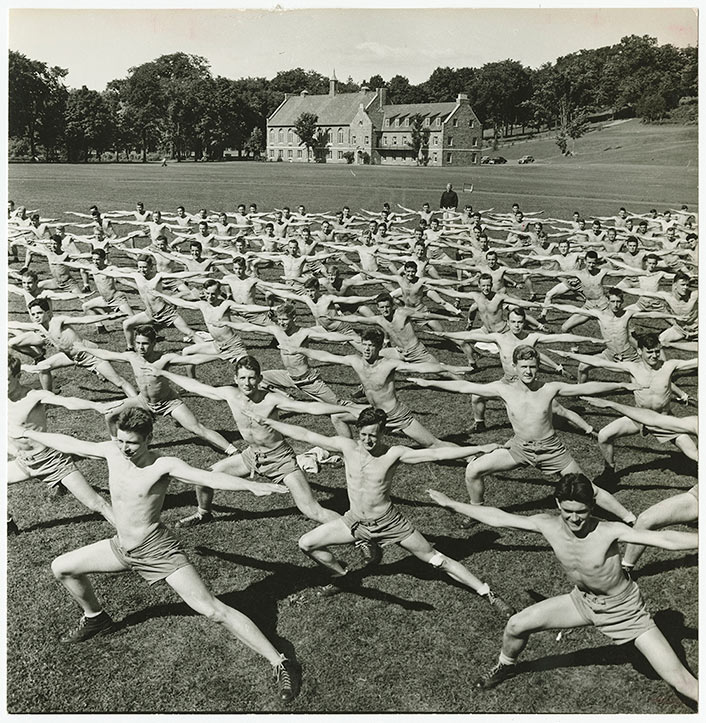

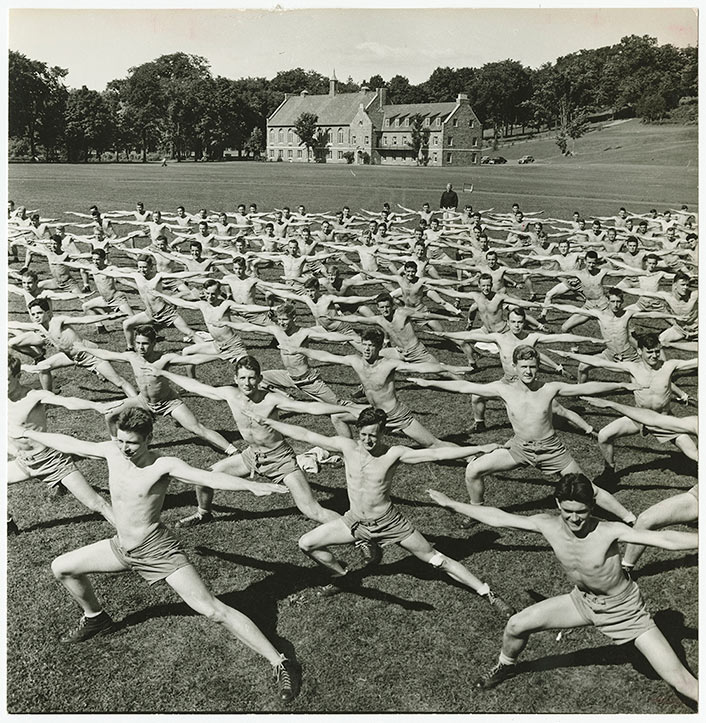

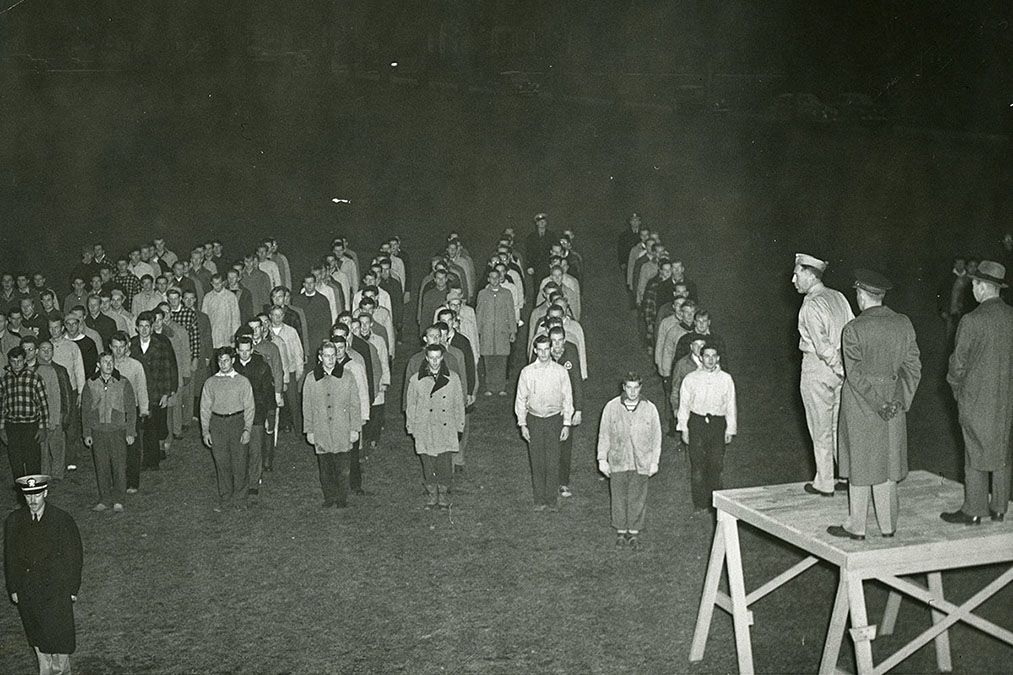

Anxiety about the war and preparation for its impact were the concerns not only of administrators, but also of students. In fact, students seemed eager to shed any appearance of coddling: “None of us want to be looked upon as leaders of a life of luxury and comfort while troops in the field and on the seas suffer the hardships… of modern warfare,” asserted an editor of the Colgate Maroon.3 And so, in October of 1942, students assembled in Memorial Chapel and voted to institute an undergraduate military training and physical fitness program. Exercises included early morning calisthenics on Whitnall Field; running up and down the steep incline behind Huntington Gym (dubbed “Agony Hill”); fencing; hand-to-hand combat; and climbing, crawling, and jumping through a 400-yard commando course while shouldering wooden rifles.

Cadets exercise on Whitnall field, circa 1943

As expected, traditional student enrollment declined from 873 students in 1942, to just over 100 by fall of 1943.4 In order to keep the university afloat, President Case set about negotiating contracts with the military to transform the existing Civilian Pilot Training program into a comprehensive Navy Flight Preparatory School (NFPS). The success of the CPT program, along with the physical education and military training curriculum initiated by the students, likely served to bolster the case to the federal government that Colgate was a ready and willing host for the Navy’s programs.

The NFPS opened in January 1943 with the first 200 cadets arriving on a troop train that had plowed its way from New York City through a heavy (though not unusual) central New York snowstorm. By March 1943, there were 600 NFPS cadets on campus ready to begin a three-month course in the study of aeronautics, as well as an intensive program of physical training. The federal government paid $50 per month for each student’s room and board and $168 in tuition, helping the college to meet its basic operating costs during wartime.

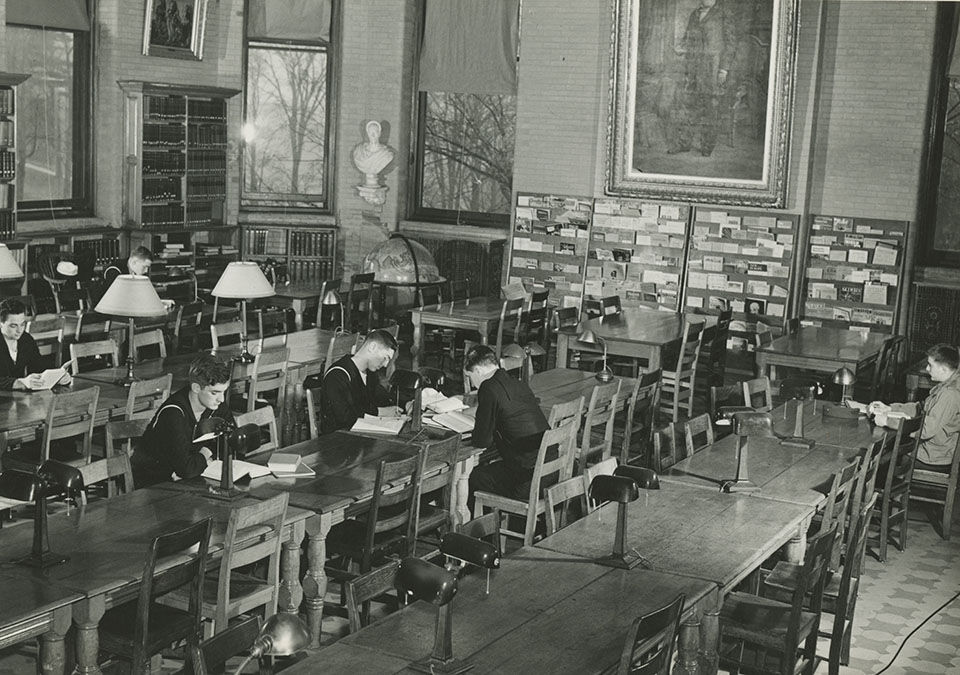

The opening of the NFPS marked a significant moment of change on campus, where for the next few years “a large proportion of the college instruction and facilities were devoted to men in navy uniform.”5 Typical coursework included classes in navigation, code, and engines. Significantly, a shortage of teaching staff, combined with bloated student numbers, caused the university to employ a handful of local Hamilton women as instructors.

Navy Flight Preparatory School cadets leave Memorial Chapel, 1943

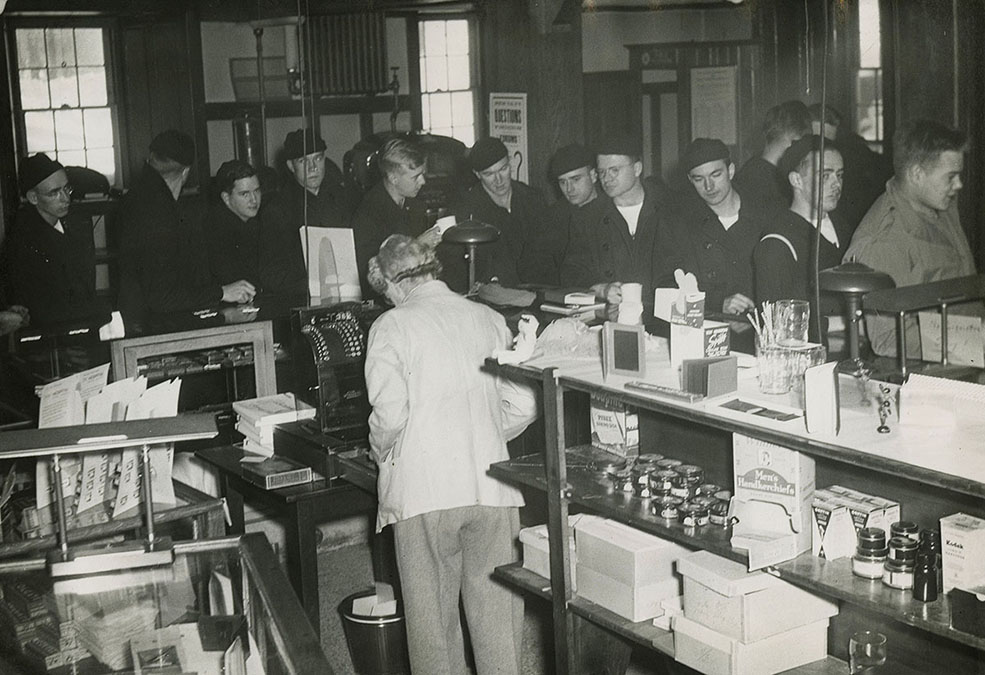

In May 1943, additional programs were announced, and each newly arrived unit of trainees was distinguished by an evolving series of letters and numbers. The Navy Reserve’s V-1, V-7, and V-12 programs, for example, enabled students to begin or continue their college studies and simultaneously receive the first phases of military training. By the summer of 1943, the student body had swelled to 1,300 students — with only 117 civilians. University facilities were stretched to their limits. With the campus bursting with cadets in training, the university struggled not only to house and feed them, but also to entertain them. Cadets played billiards in James C. Colgate Hall, then the Student Union and de facto student military headquarters. They sipped Coca-Cola at the soda fountain in the campus store, or Co-op, located in East Hall. Music and theater gained in popularity, and young men formed 10-piece bands and singing groups such as the Colgate Thirteen (created in 1942); broadcast variety shows on local radio; and arranged all-college formal dances, where women and men became acquainted via conga lines and punch bowls. Students also journeyed into Hamilton proper for movies at Schine’s State theater and for general conviviality at the local USO, located at the corner of Broad and Payne Streets.6

With President Truman’s announcement of Victory in Japan, on VJ Day in August 1945, students, professors, and townspeople gathered in Memorial Chapel for a service of “jubilation and thanksgiving,” followed by a campus holiday.7 The university began planning its move back to a peacetime college, with the final group of Marine and Navy trainees leaving Hamilton in June 1946. The 1947 Salmagundi (the first published since going on hiatus at the start of the war) was contemplative in an editorial: “Colgate had done its job… For more than three years, Colgate had seen uniformed men in its classes and on its campus. Now, relieved of its war duties, the University looked ahead to even greater tasks in a time of peace.”

Colgate had done its job… For more than three years, Colgate had seen uniformed men in its classes and on its campus. Now, relieved of its war duties, the University looked ahead to even greater tasks in a time of peace.”

Salmagundi, 1947

Colgate’s “Flying Red Raiders” airport in Bouckville, N.Y., 1943

Navy Flight Preparatory School cadet starts airplane by turning propeller, 1944

Cadets climb wall on 400-yard commando course, 1943

Student Corps dressed warmly for early morning drills on Whitnall Field, 1942

Student Corps practice hand-to-hand combat, 1942

Bill Geyer, Class of 1942, leads cadets up the ski slope, dubbed "Agony Hill," 1943

Navy Flight Preparatory School cadets arrive at Hamilton train station during snowstorm, 1943

Navy Flight Preparatory School cadets receive Navy-issue bedding, 1943

Cadets study in James B. Colgate Library, circa 1943

Navy Flight Preparatory School instructors: Mrs. Audrey Shirley; Mrs. Robert Edwards Mills; and Alice Rogers, 1943

Cadets browse merchandise at campus store in East Hall, 1945

Members of a Marine cadet band perform on stage for student event, 1943

Notes & Sources

- Cutten to Board of Trustees, Colgate University World War II records, A1057, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Everett Needham Case papers, A1015, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- “Military Matters,” Colgate Maroon, October 16, 1942

- Enrollment reports, 1942–1949, Colgate University Dean of the College records, A1004, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Carl A. Kellgren, “Colgate University in World War II,” Colgate University World War II records, A1057, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- “Colgate at War,” Salmagundi, Hamilton, NY: Colgate University Press, 1947

- “Campus joins village in celebration of war end,” Colgate Maroon, August 15, 1945

- The Colgate Maroon and Colgate Maroon News, A1165, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Colgate University Dean of the College records, A1004, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Colgate University World War II records, A1057, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Everett Needham Case papers, A1015, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Media collection, A1061, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Salmagundi records [yearbooks of Colgate University], A1288, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Smith, James Allen, Becoming Colgate: A History of Colgate University. Hamilton, N.Y.: Colgate University Press, 2019

- Williams, Howard D., A History of Colgate University 1819–1969. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1969

All images from Colgate University World War II records, A1057, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University