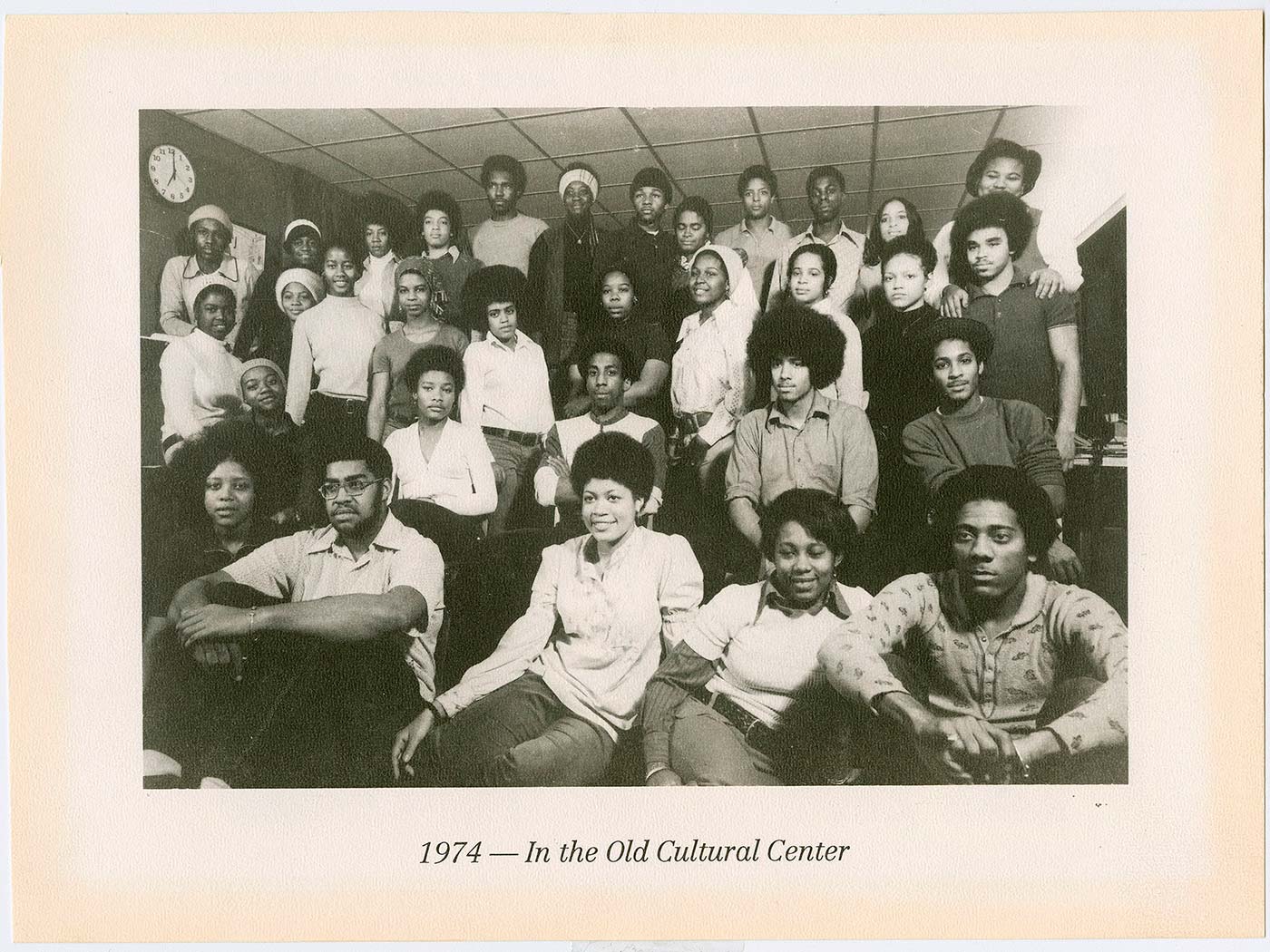

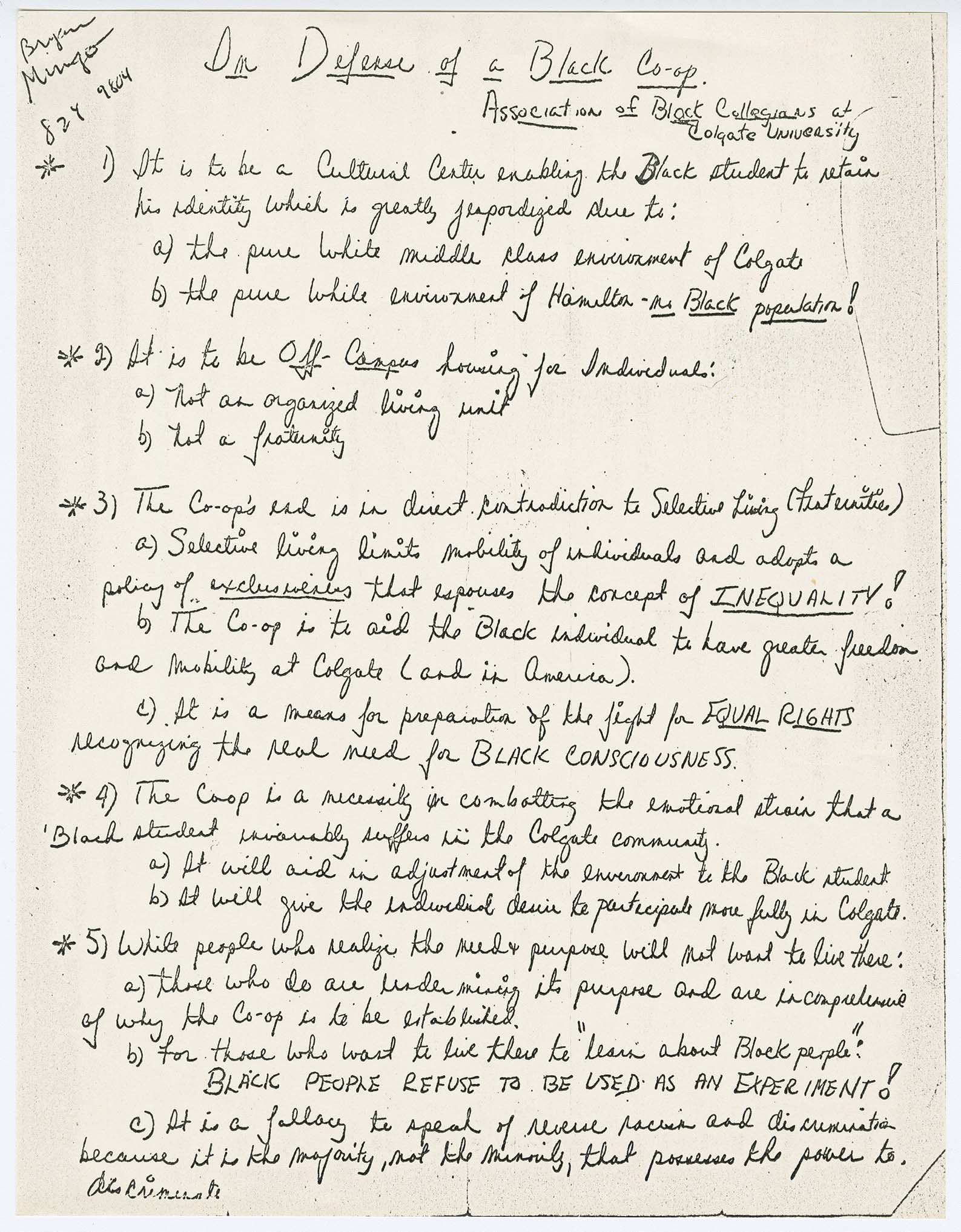

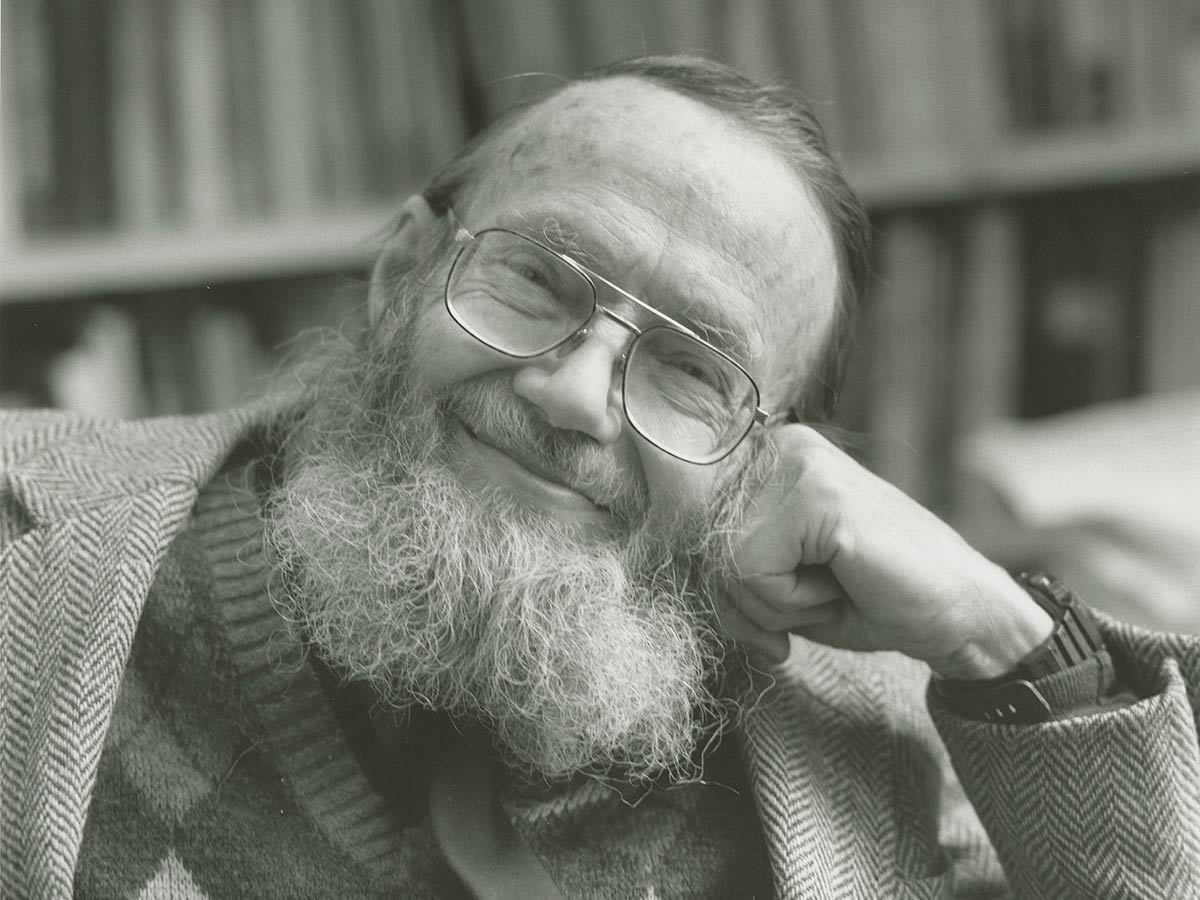

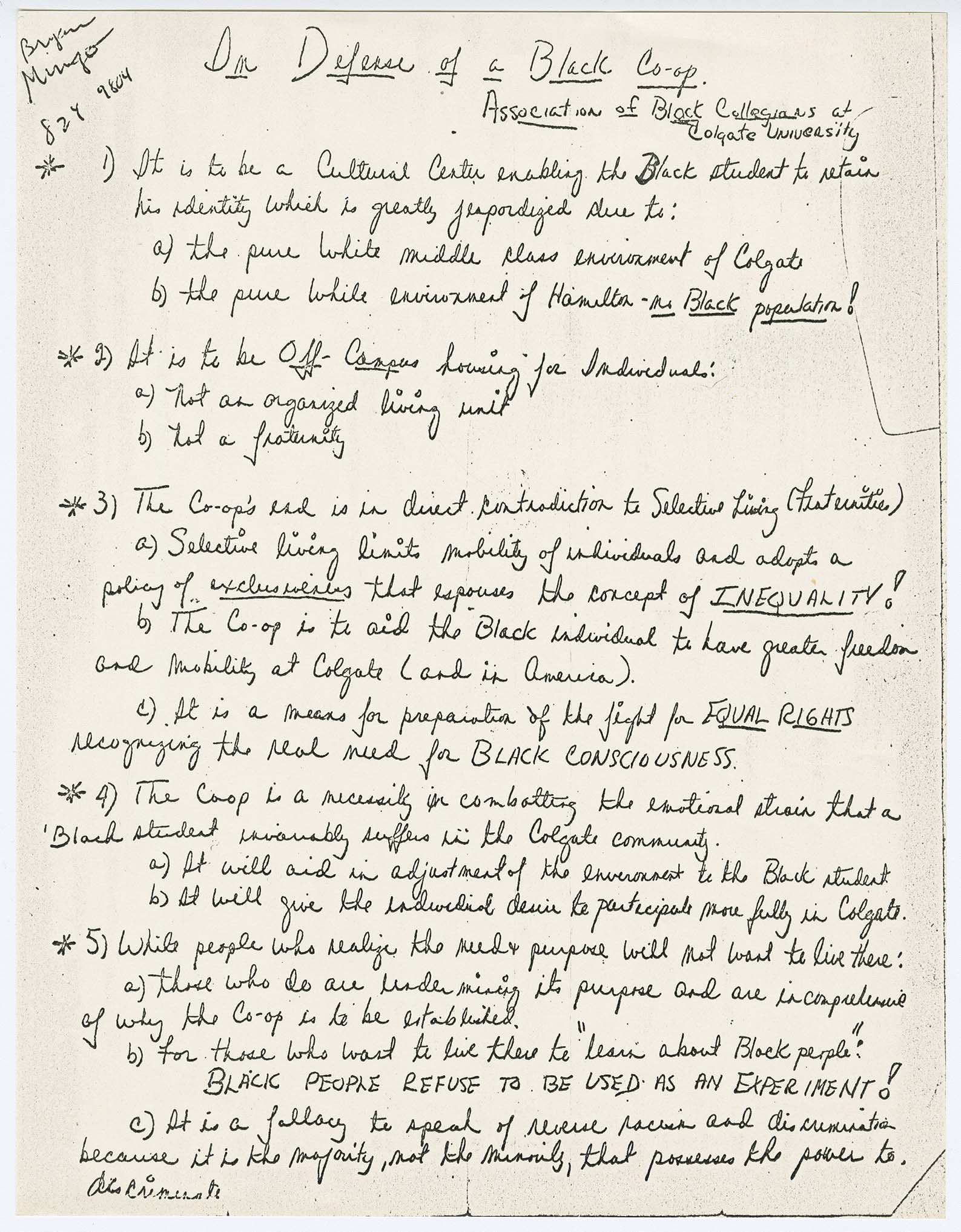

“In Defense of a Black Co-op,” memo from the Association of Black Collegians, 1969

Discussions of the need for a “black co-op” or cultural center began just before the 1968 administration building sit-in, when the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) submitted a recommendation to the university with four points of issue:

- That the university assist in establishing a cooperative residential center for black students

- That the university introduce a required course in black history

- That the university intensify its search for qualified black personnel, both administrative and faculty

- That the ABC be represented in the Student Senate1

For the cooperative center, the ABC envisioned a space that would include a communal gathering area, residential rooms, and a library, with the ambition of improving “the quality of life and education for black people in a white man’s college.”2 The students also underscored the need for a place in which they would be relieved of the psychological and emotional strain invariably felt by students of color within a white, upper-middle-class community;3 however, the university struggled to fund the center and to choose an appropriate building for its location. Officials first suggested Taylor House (once the home of second president Stephen Taylor, then being used as a biology laboratory), but renovation estimates were considered too costly. Olmstead, Griffith, and Clark houses were also considered, but rejected.

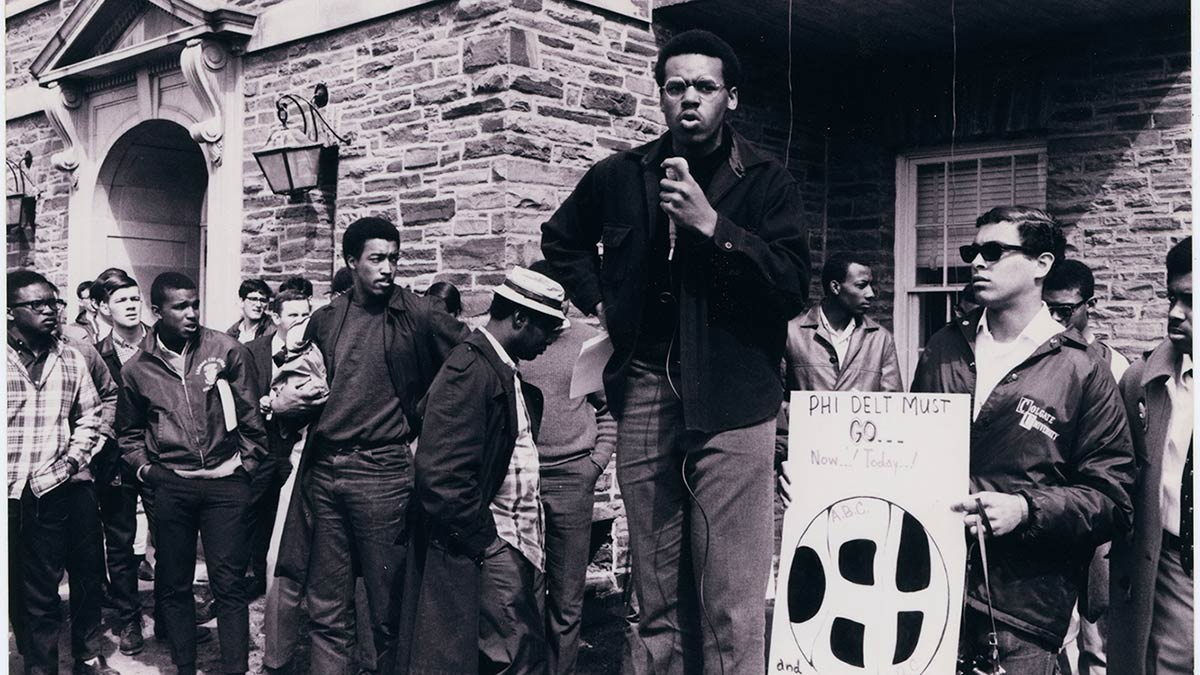

An incident on March 20, 1969, revealed that racism was persistent in the community when two black students were attacked by “10 white town folk” in the village of Hamilton.4 The attack seemed to put into relief the slow progress of the university in regards to the ABC’s four proposals the previous April. The group once again decided they needed to act and focused their energies on the establishment of a cultural center. On April 25, 1969, the ABC led a peaceful protest and sit-in at the faculty club, Merrill House. The ABC claimed, a bit tongue-in-cheek, that if plans for a cultural center could not be solidified, they would simply take over the faculty club for their needs. The Board of Trustees and the Educational Policy Committee issued an injunction against the students and threatened the involvement of outside law enforcement, citing a resolution passed after the 1968 sit-in. (The resolution stated that “individuals or groups who engage in acts which disrupt or interfere with the functioning of the university...may be subject to suspension, civil injunctive action, or… prosecution for contempt of court.”5)

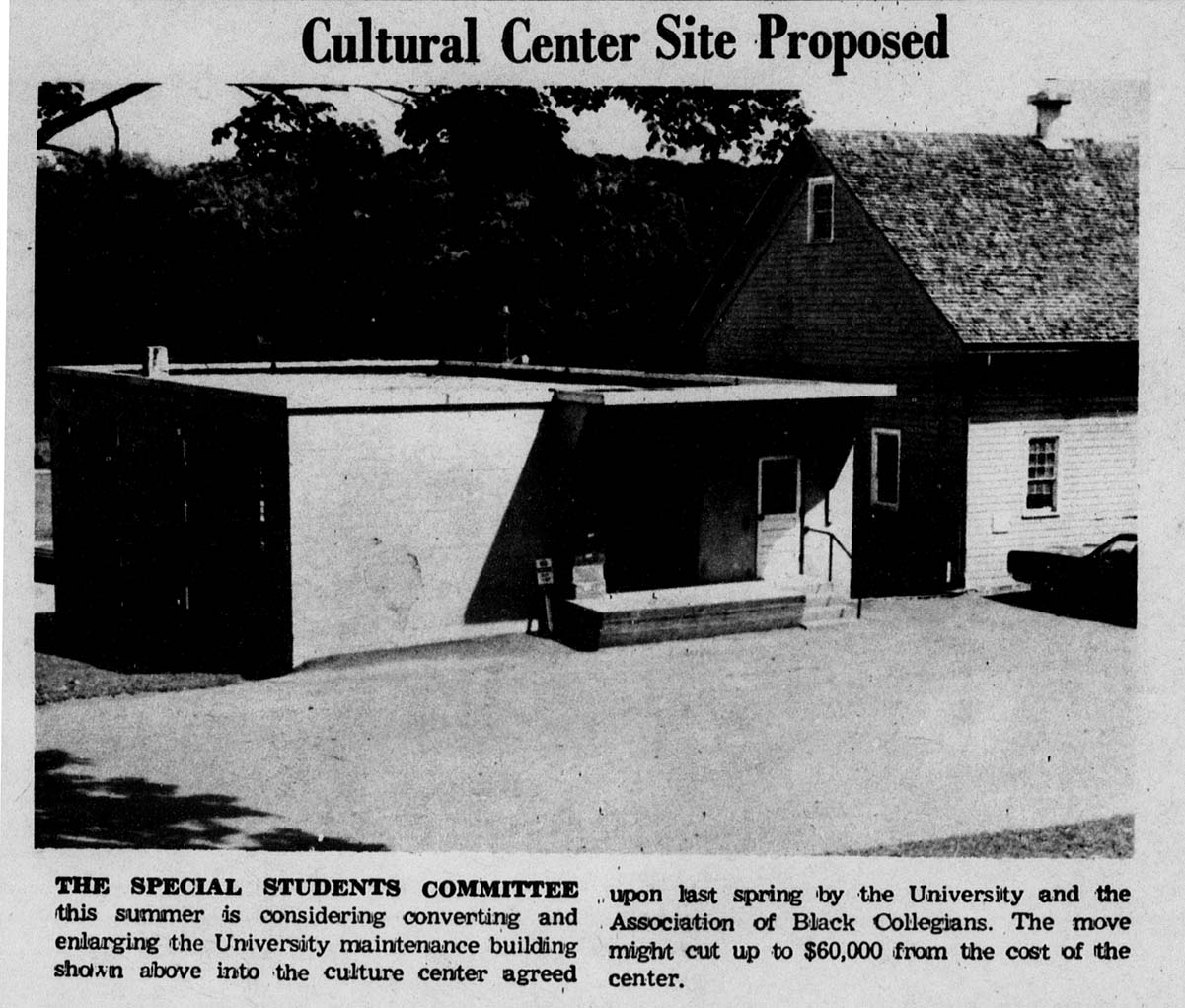

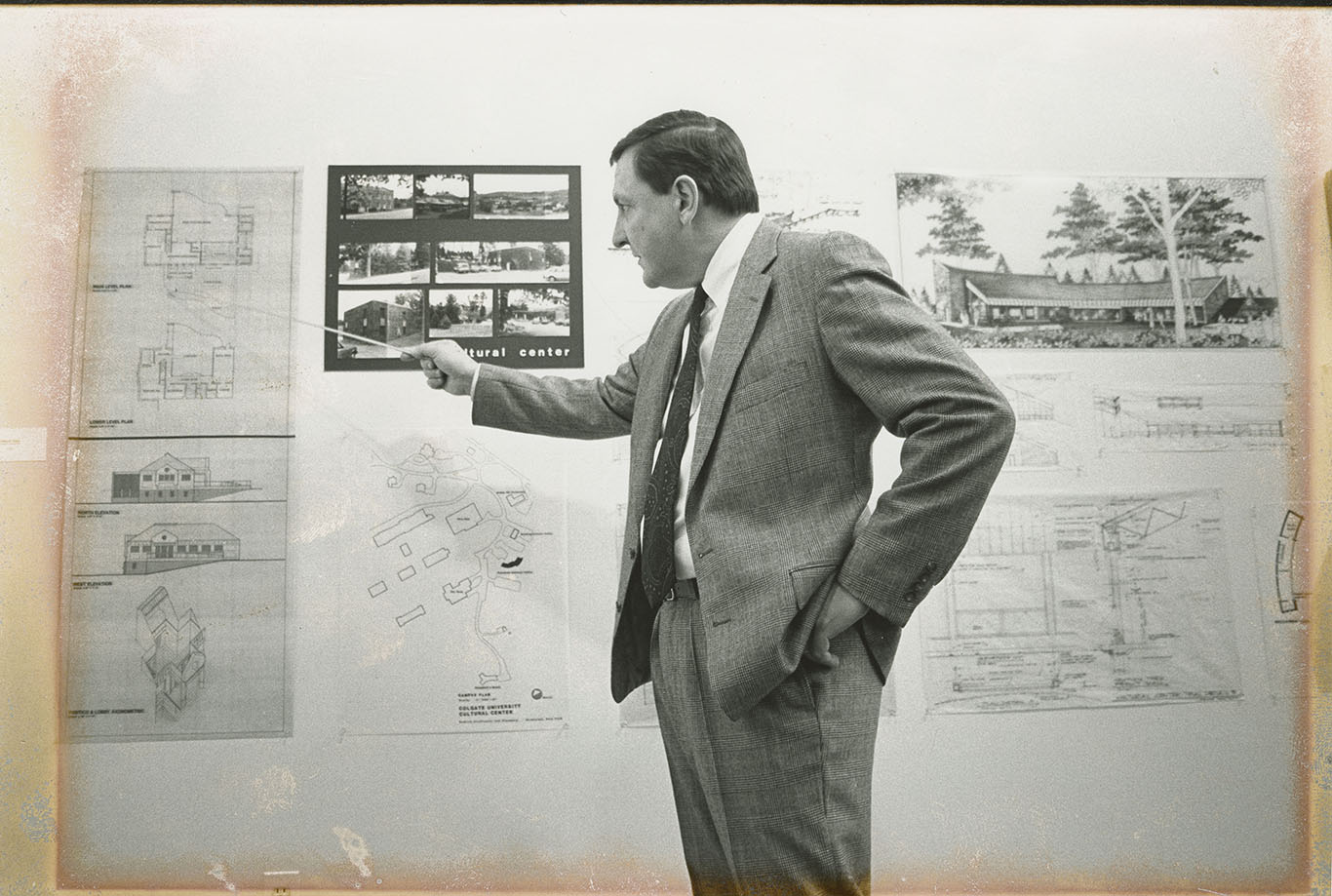

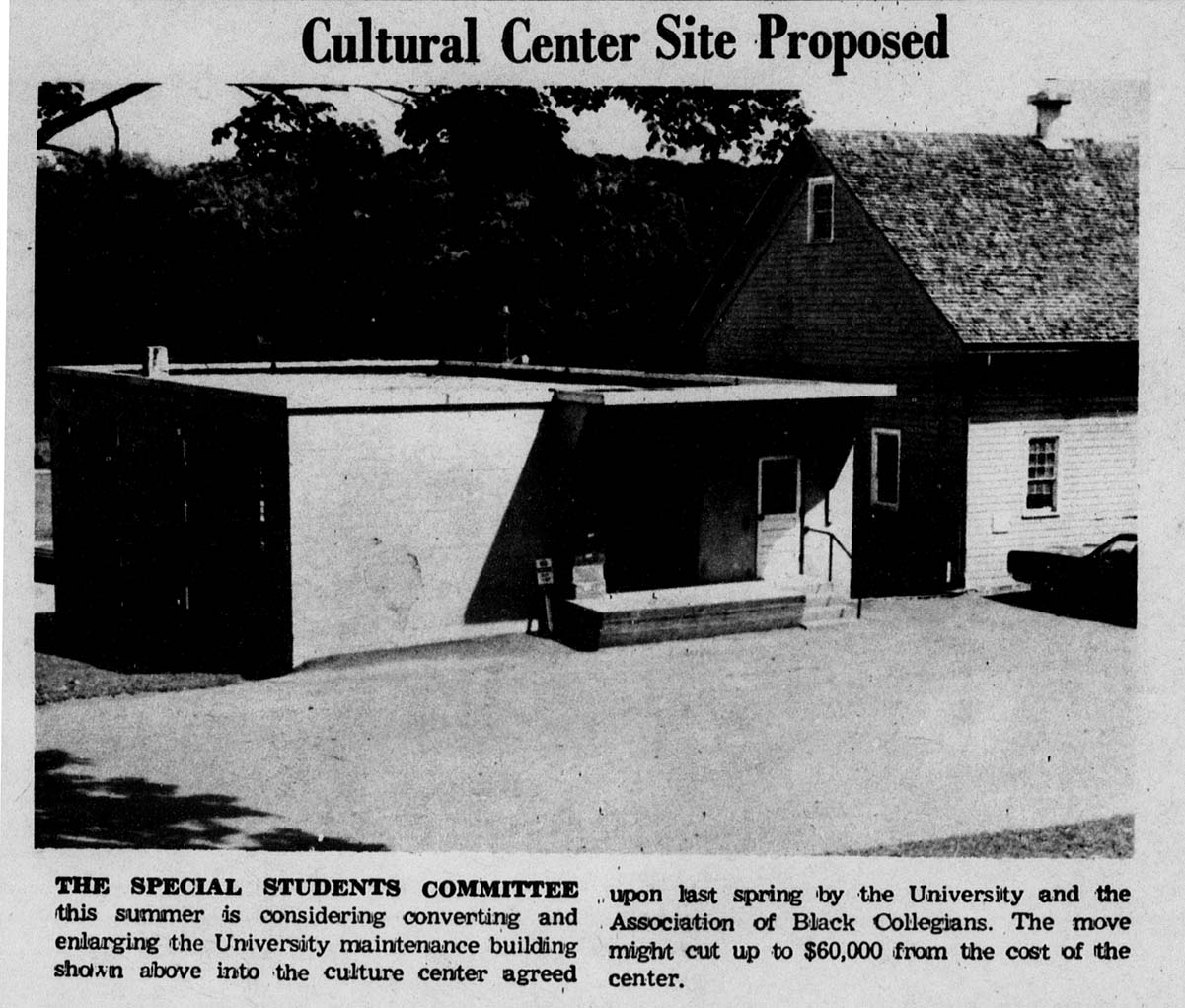

Maintenance building is proposed as site for cultural center, August 1969

Following the threat of legal action, 1,200 Colgate students rallied in Memorial Chapel in a show of solidarity with those occupying Merrill House; they loudly rejected the introduction of outside forces to resolve the protest.6 President pro tem Franklin Wallin decided to delay legal action and began negotiations with the ABC members. The parties agreed to split the costs of a cultural center: the university would provide $50,000 and the ABC would raise another $50,000.

Unfortunately, estimates for building a new center came in at over $200,000 and students were again left in the lurch wondering where the funds would come from.7 The university’s budget, as well as its priorities as an institution, were in a state of flux with the installation of a new president, Thomas Bartlett. In an effort to resolve the problem quickly, Bartlett proposed the renovation of a maintenance building — a “green cinderblock” structure — for the site of the center.8 Undoubtedly, this was not quite the space the students had hoped for. But it was used as the cultural center for nearly 20 years and hosted a number of key figures in the civil rights movement, including Adam Clayton Powell, Class of 1930, Ralph Abernathy, and Muhammed Ali, among others.

In 1985, the Minority Affairs Committee, a committee composed of students, faculty members, and administrators, began developing plans for a new cultural center. Subsequently, Leroy Potts, Class of 1985, founded the Alumni of Color Organization, which provided vital assistance in generating support, guidance, and capital for the project.

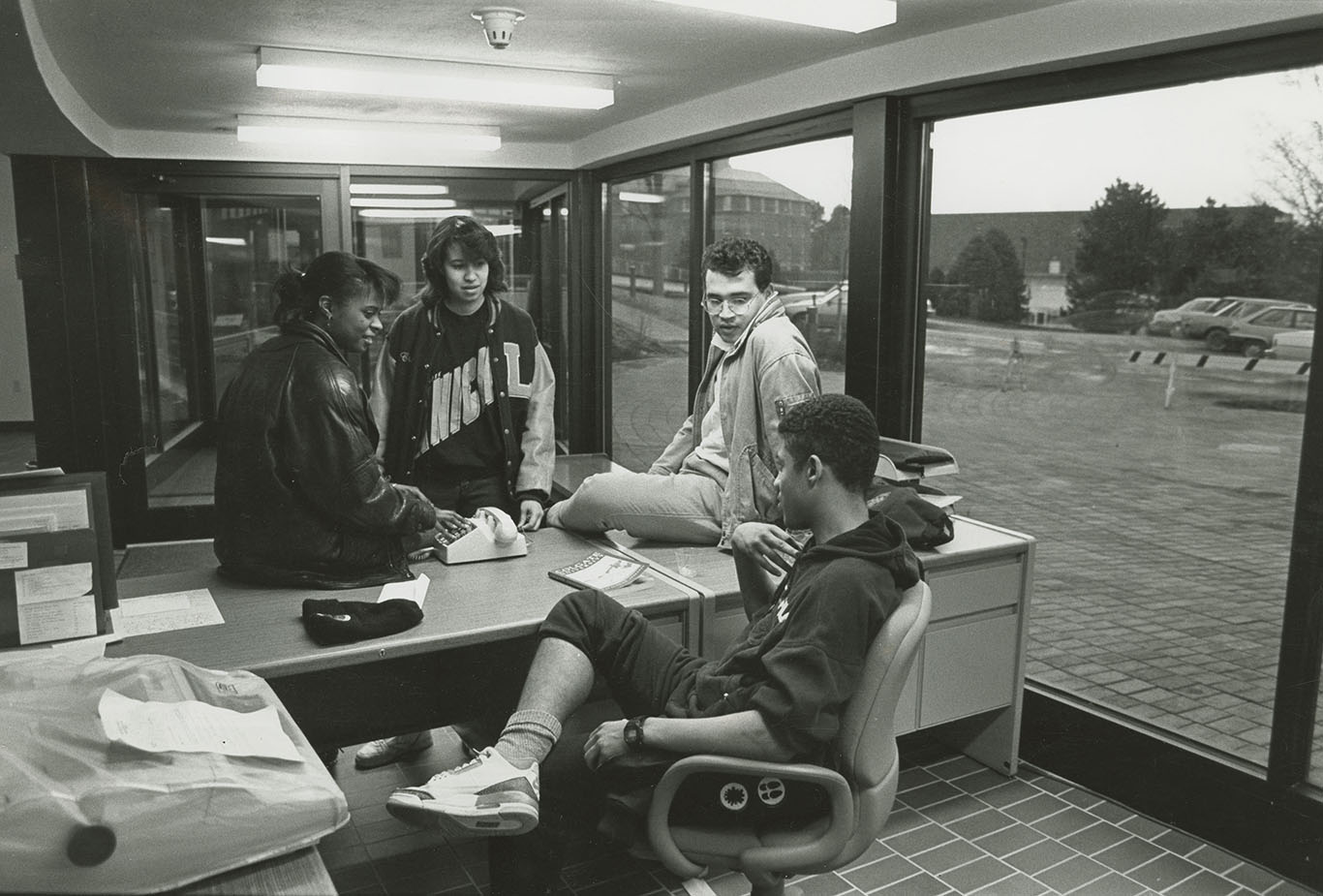

A site was proposed at the location of the old golf course, on the upper hill of campus overlooking the Chenango Valley. In April 1989, the center opened at its present location: a modern building with large panes of curved glass, complete with a multipurpose room, kitchen, music room, and library. A plaque unveiled at the center’s opening reflects the years of struggle by students and alumni to bring the venue to fruition; it reads: “Dedicated to those brothers whose vision, determination and sacrifice to the ideals of cultural and ethnic diversity provided the foundation for the Cultural Center’s reality.” Todd Brown, Class of 1971, and the center’s second director, noted that the venue had transformed from “a safe haven for African American students” into a “thriving community venue for all people of diverse backgrounds.”9

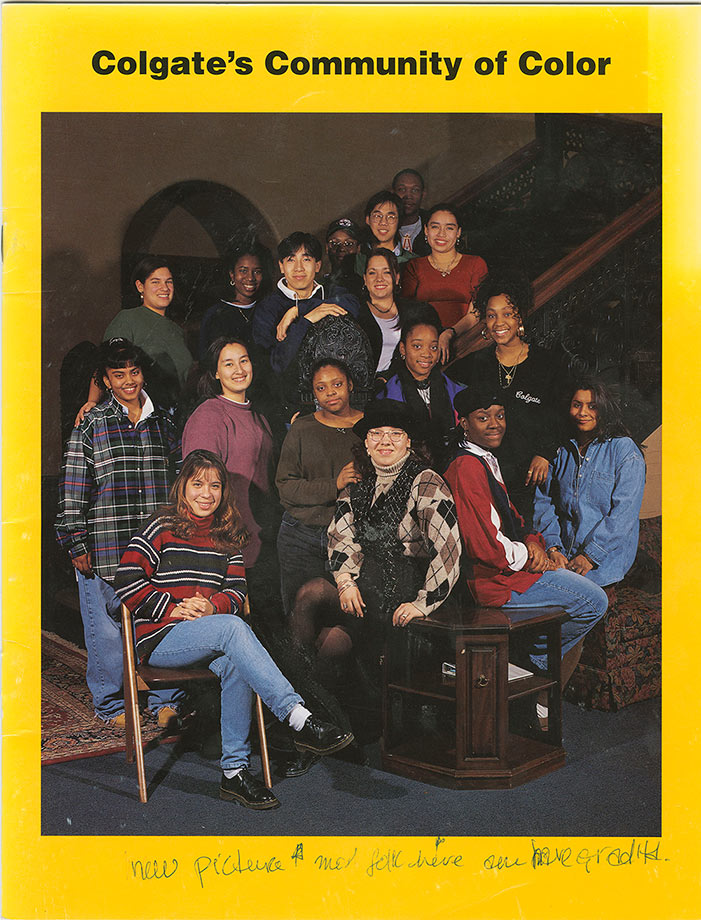

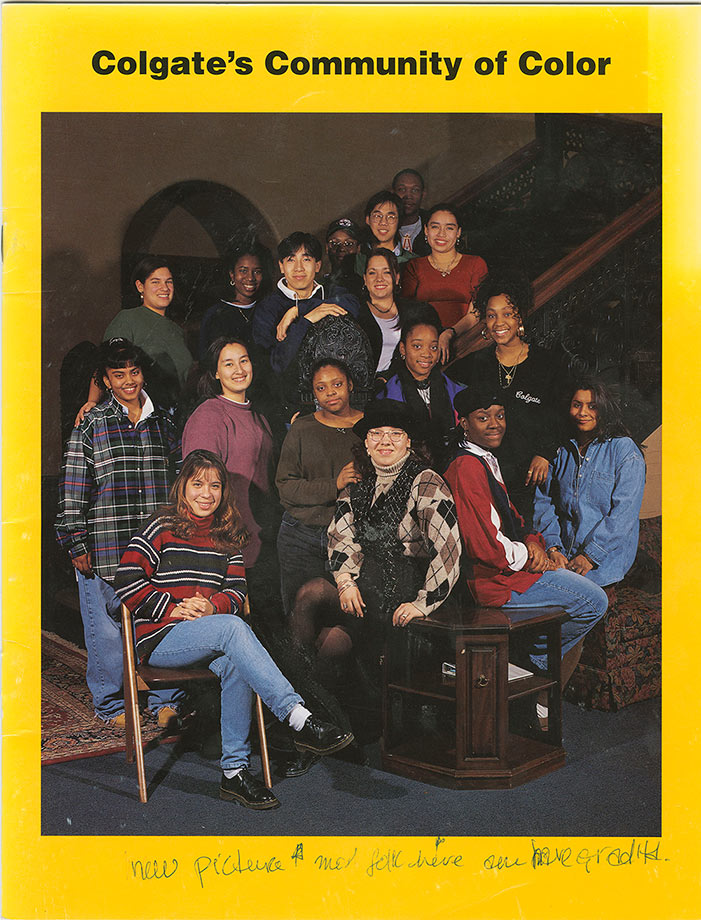

Cover of “Colgate’s Community of Color” brochure, 1993

In 1996, the center was renamed the Africana, Latin, Asian, and Native American, or ALANA, Cultural Center as a result of students’ suggestions that the building reflect the communities and purposes it represents.

At the time of the university’s Bicentennial, the center is home to 22 student groups, such as the Black Student Union, the Korean Culture Association, the Latin American Student Organization, Queer and Trans People of Color, and others. These groups collaborate to promote a large range of events, speakers, and workshops, including the annual ALANAPalooza, a fall semester kick-off barbecue set on the venue’s spacious patio. Other popular events include heritage month celebrations, brown bag lunches, Holi festival, and Martin Luther King Jr. week.

The ALANA Cultural Center flourishes as a learning center and focal point where students, professors, and staff members gather to understand the Africana, Latin American, Asian American, and Native American cultures, their struggles, and accomplishments.