Jane Lagoudis Pinchin, Thomas A. Bartlett Chair and Professor of English, emerita, reminisces about being one of the first two women hired to teach full-time at Colgate and about the pioneering women of the faculty. This essay is an adaptation of her talk, “Enter Women at Colgate,” which she presented as a commencement seminar on May 19, 2018, on the occasion of receiving an honorary doctor of letters degree from Colgate, and again as part of Colgate’s Bicentennial celebration kickoff week in September 2018.

In “Three Guineas,” her 1937 essay, Virginia Woolf writes about academic ceremony — inaugurations, convocations, commencements, and bicentennials, if you will — and about what higher education has to offer women, who in her time, perhaps in ours, had not had an equal share in the enterprise:

“...we have to ask ourselves, here and now, do we wish to join that procession, or don't we? On what terms shall we join that procession? Above all, where is it leading us, the procession of educated men? … Let us never cease from thinking — what it is, this "civilisation" in which we find ourselves? What are these ceremonies and why should we take part in them? What are these professors and professions and why should we make money out of them? Where in short is it leading us, the procession of the sons of educated men?”

Examining a bit of the history of women at Colgate, we will try to answer Woolf, or at least to talk with her, about women’s place in the academy from the perspective of those who have taught, and, indeed, led this faculty at Colgate University.

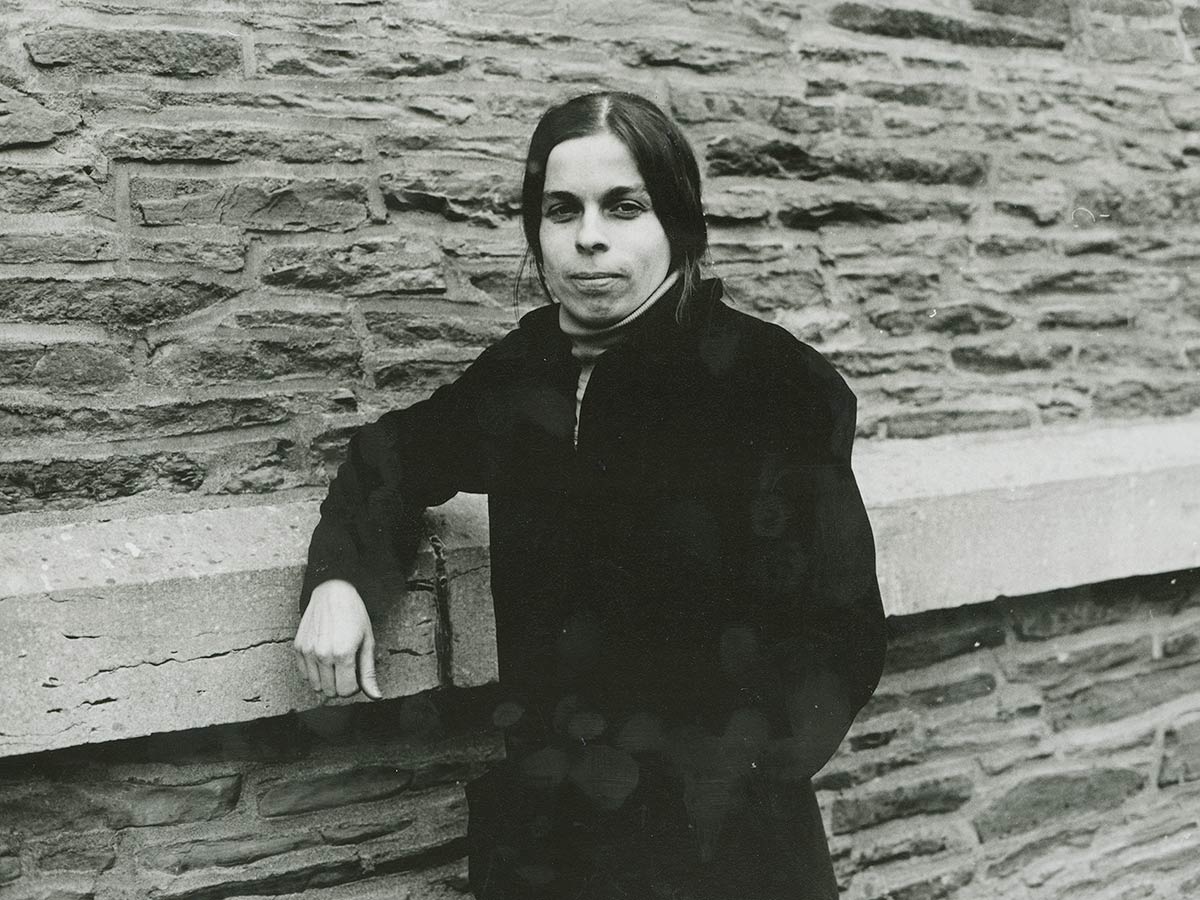

I begin with some sense of my own start as one of the first women teaching on this hill. A bit of biography.

Freshman mixer, 1965

I came to teach at Colgate, first, in 1965.

I interviewed for the job aged 22, younger than almost any faculty member who applies for work now. The interview was arranged by my graduate school adviser, the chair of the English department at Columbia University, who in his office asked me whether I wanted to teach at Colgate, where, he said, the chair of the English department had been a student of his. He said, as I remember it, “If you want the job, it’s yours; it’s amazing the power that rests in this seat.” The call was made. And I traveled to Hamilton to meet a number of people, including the well-known Emerson scholar (and that former student) Joe Slater (to my right in the photograph), and a jovial man called John Hoben (on my left in the photograph), who winked and asked me whether I thought I could handle a class of young men.

I was hired by the English department to teach Core 17, a literature course in the general education program — a course that all members of the faculty taught, but some very junior faculty, like me, taught exclusively. I came to Colgate as one of the first two women hired in a full-time position from outside of the community. The other woman, Johanna Henry, was in the German department. We were both hired at the rank of instructor.

What did this young woman, my young self, Manhattan-born-and-bred, see when she first drove to Hamilton in a used Plymouth Valiant she’d bought weeks before, just after learning to drive? A campus, a landscape, greener and more manicured than she could imagine. And what seemed a world of white, blonde men (to her eye), right out of the movie The Graduate.

My car broke down on my way to my very first class and, abandoning it, I ran up the hill, and into a room where I was to teach Aristotle’s Poetics from a common syllabus. The first hand up had a question meant to do me in, about ancient Greek homosexuality. Somehow it all seemed deliciously naive, a challenge to authority that was funny and fine. Everything worked after that.

I stayed for a year, and then went back to New York to teach at Brooklyn College and finish my PhD. At Colgate, I had met the man who was to become my husband, Hugh Pinchin, and when we married I returned to teach here — where I certainly would not have gotten a job (even the part-time one that was then offered me) had I not been hired previously as a single person. Such were the nepotism laws (laws against spousal hires) then active everywhere in the United States.

But 1969 was not 1965.

“The Year of the Woman”

The world had exploded in the intervening time. The late ’60s and early ’70s saw cataclysmic changes everywhere, change in which universities like this one, and the students who attended them, were involved in protests and marches that accompanied the civil rights movement, the reaction to the Vietnam War, and a draft that didn't end until 1973. We saw ourselves and our peers as participants in the demonstrations on campuses, and as participants in the women’s movement. All this came through our front door.

We were also standing in one place — in this place — part of what it is only a little bit pretentious to call a revolution. Here and across the United States, the movement of colleges that were all-male when we came, all-male in their student body and in their faculty, were suddenly changing.

Nor is that revolution marked by the coming to Colgate in the 1960s of women like Wanda Warren Berry (philosophy and religion), or Liz Brackett (chemistry), or me, who began here in the 1960s: a story told by Wanda in two startling articles that describe her beginning as a fully credentialed academic who was offered a job grading papers for her male peers.

Or even by the coming to Colgate of the historian Carol Bleser, the first woman to be hired as an associate professor, in 1970.

The signature year, the “1819 moment” for women at Colgate, happened just a bit later: in 1974, when Colgate graduated a class that for the first time included women students, like Gloria Borger ’74, P’10, and Diane Ciccone ’74, P’10 (both later members of the Colgate Board of Trustees).

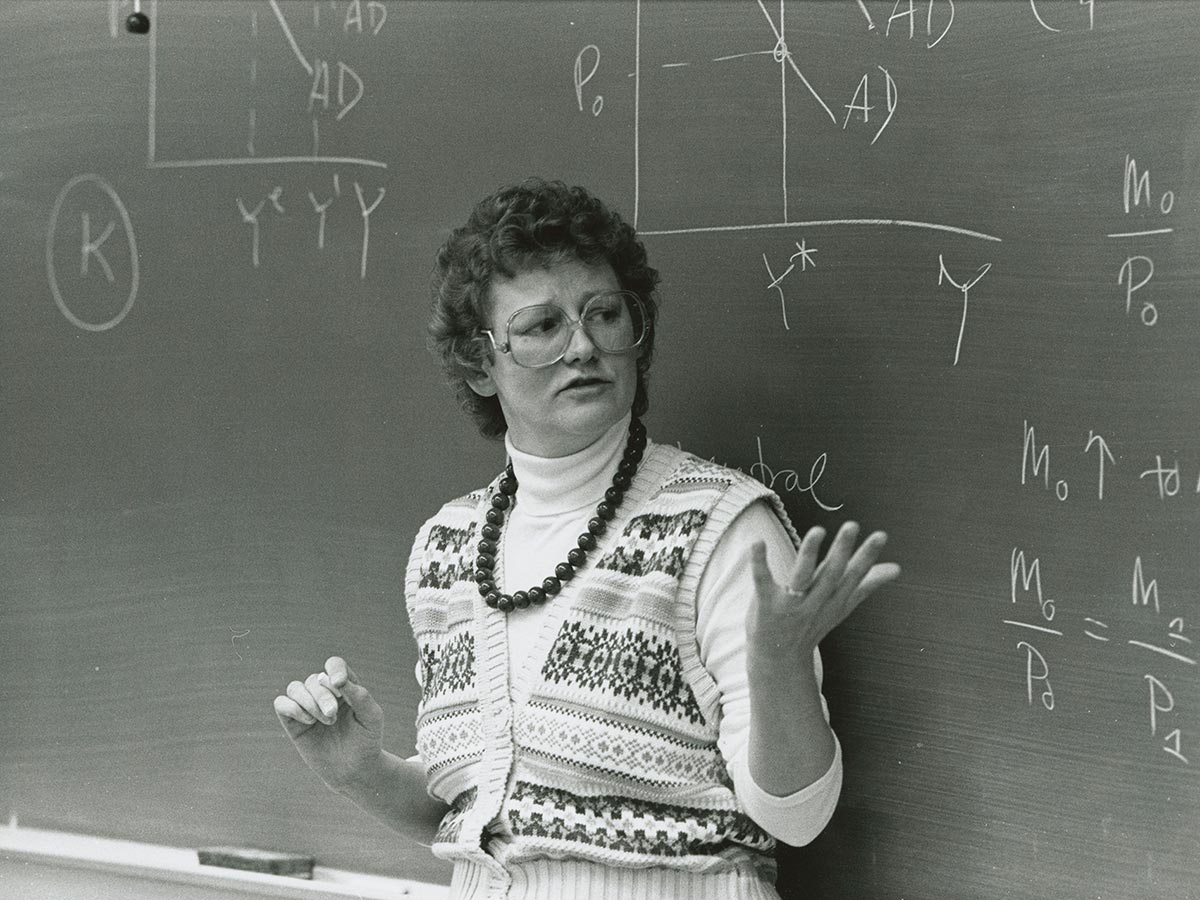

These were years when women were for the first time hired in numbers into tenure-track faculty positions on this faculty: Margaret Maurer (English), Lynn Staley (English), Myra Smith (psychology), Mary Bufwack (sociology and anthropology), Martha Olcott (political science), Marilyn Thie (philosophy and religion).

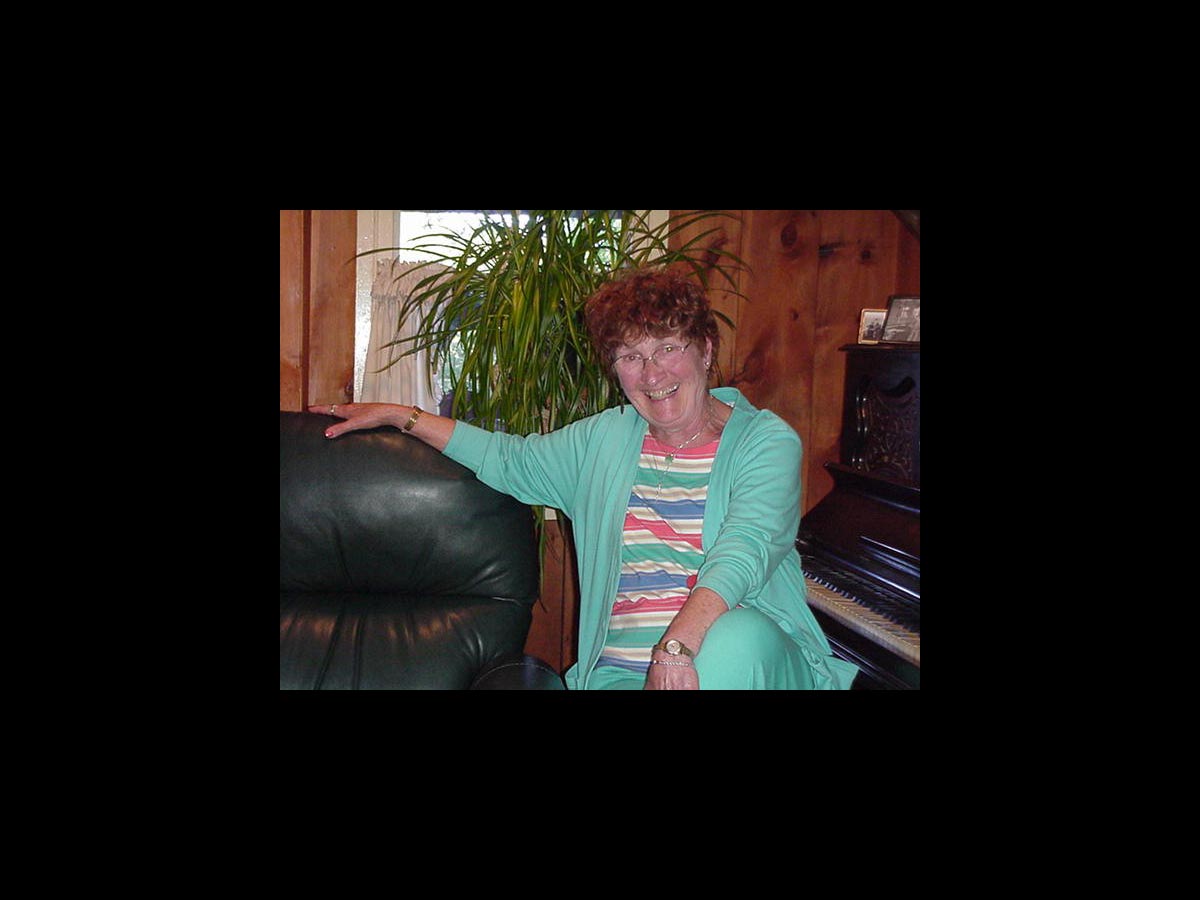

Mary Bufwack

Sociology and Anthropology

1974–1981

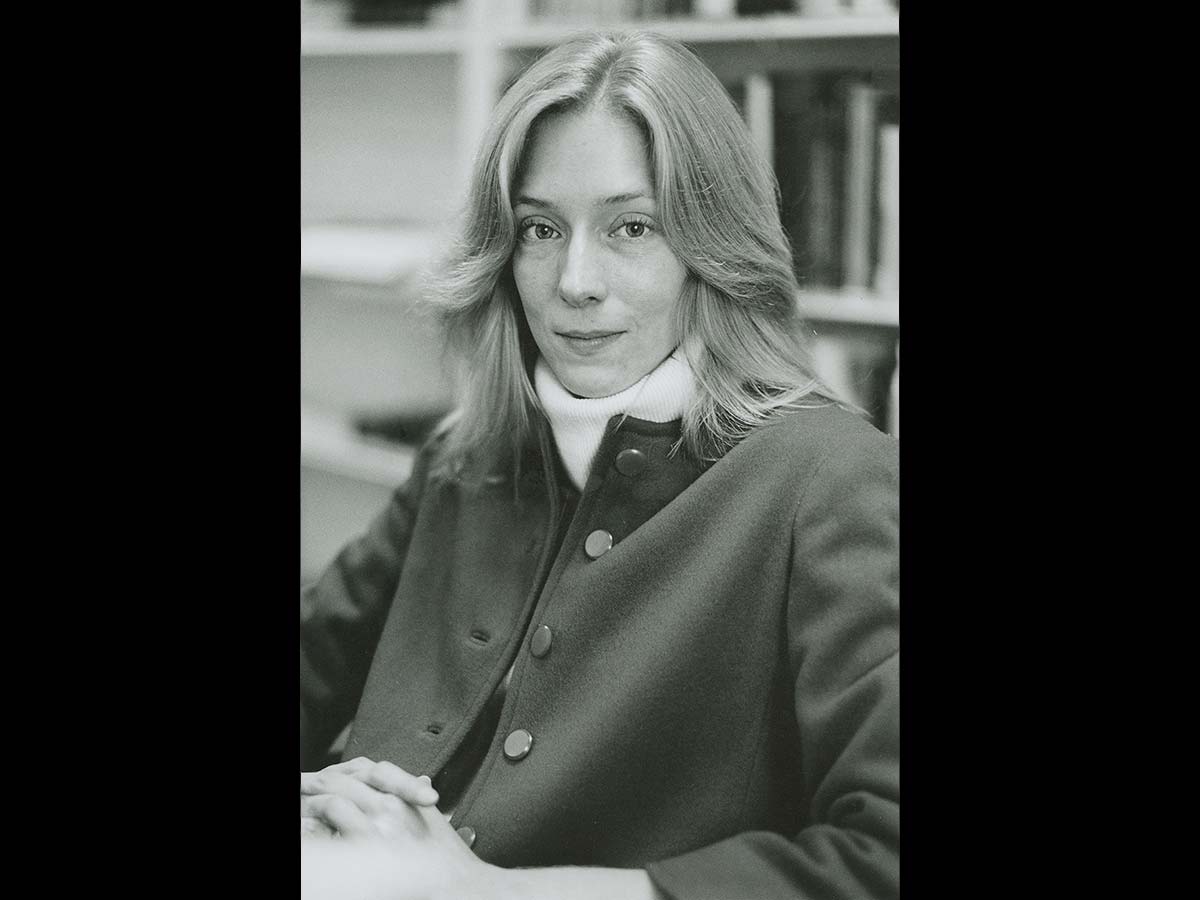

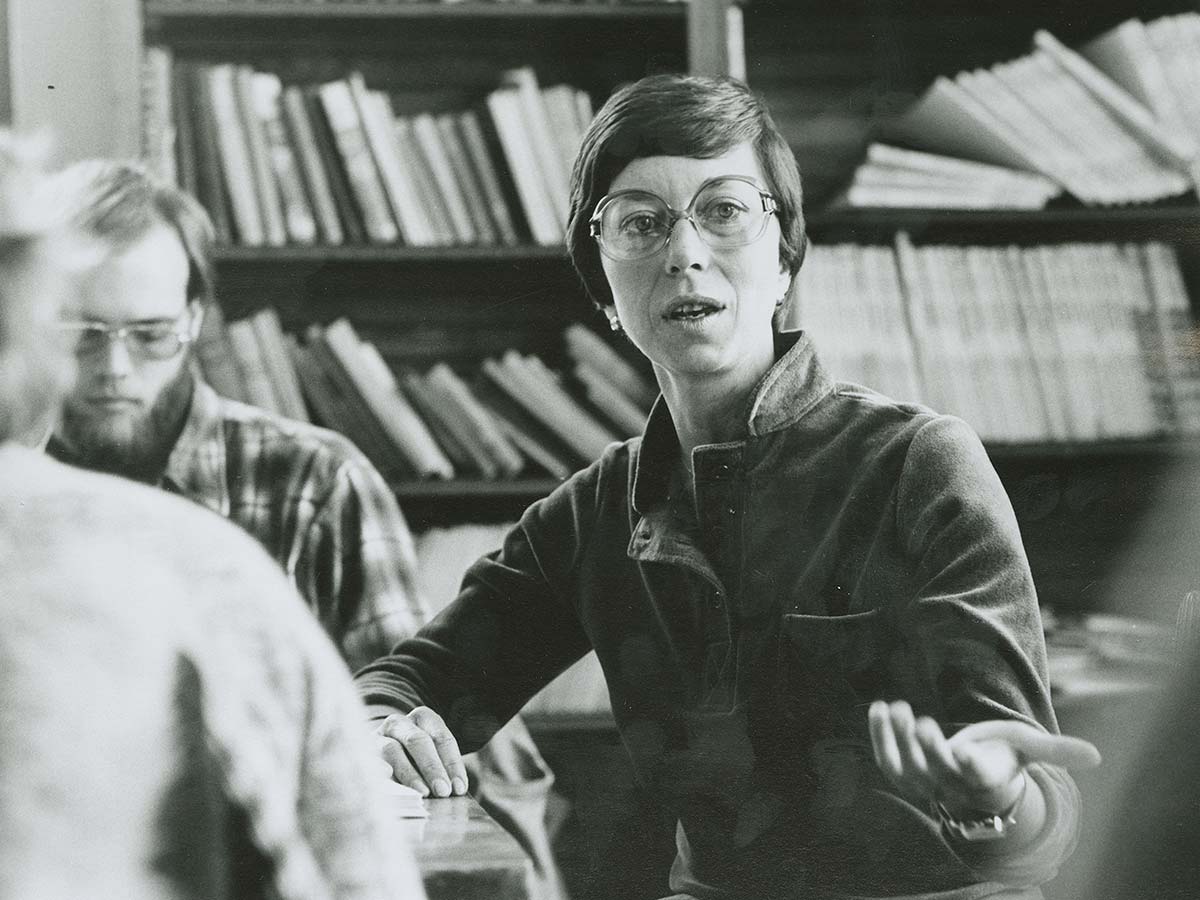

Margaret Maurer

English

1974–

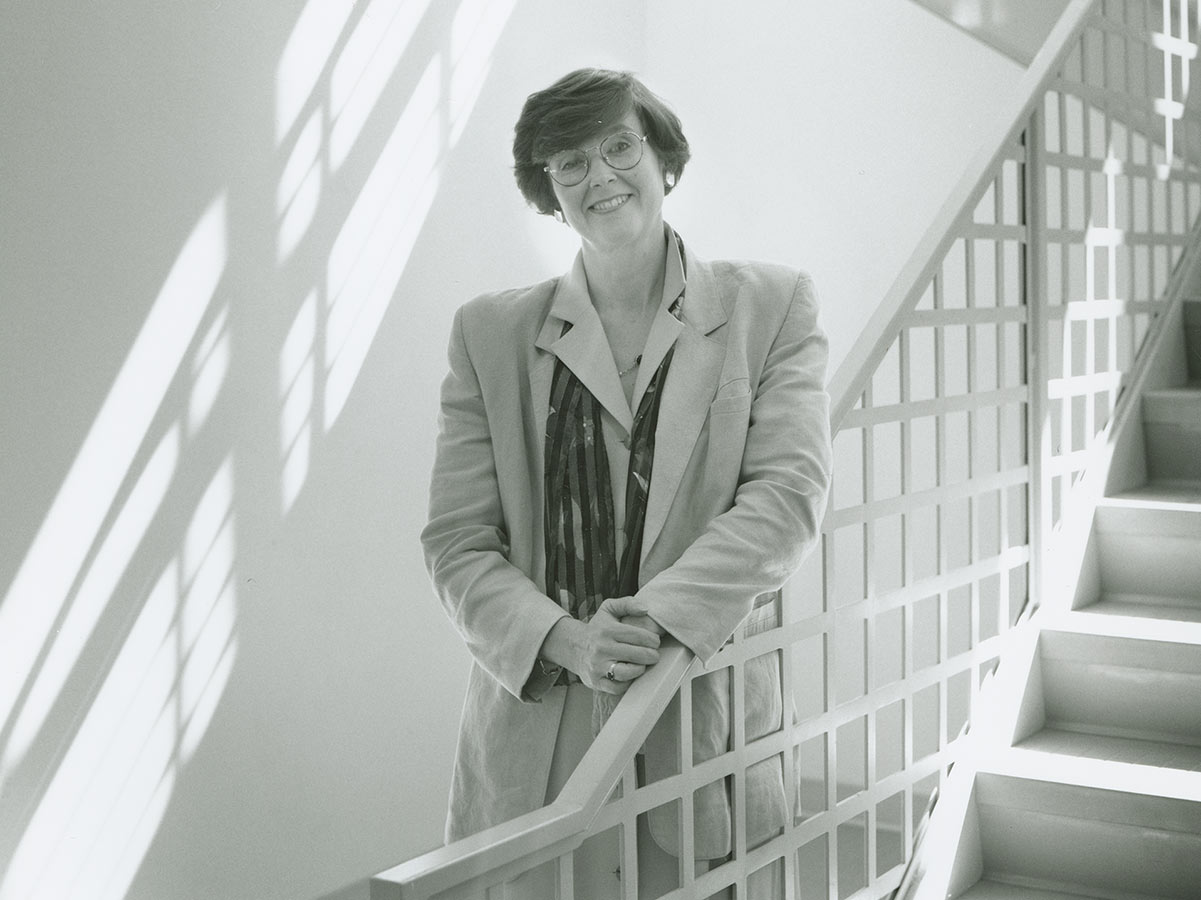

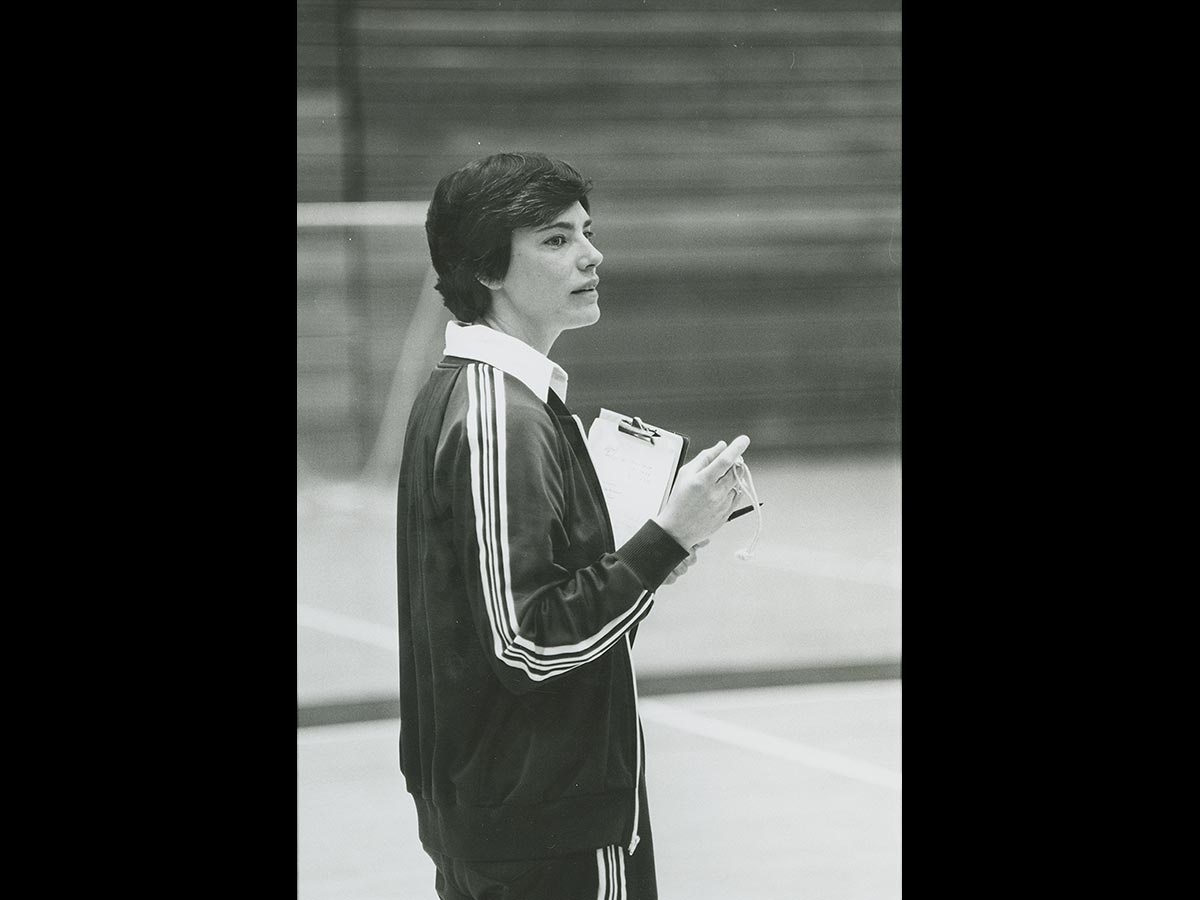

Martha Olcott

Political Science

1974–2001

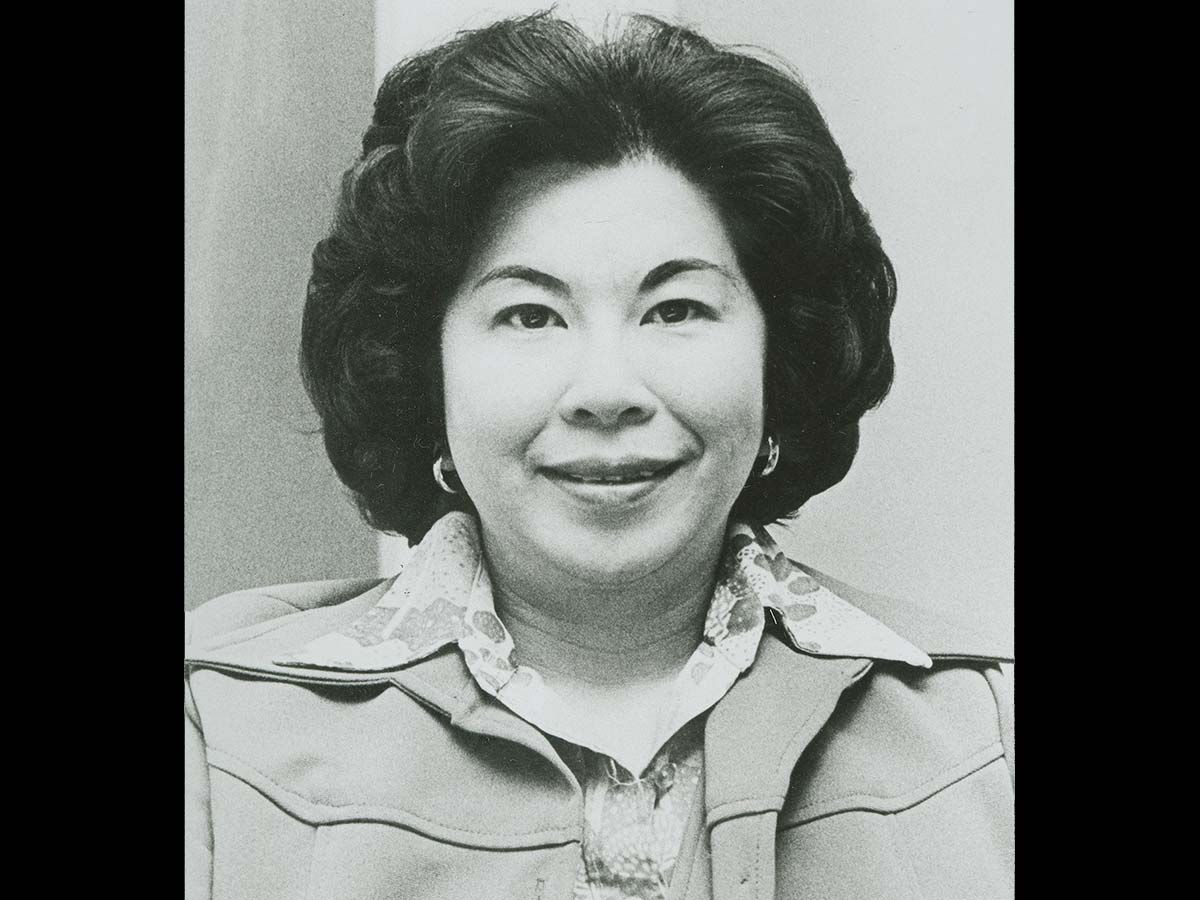

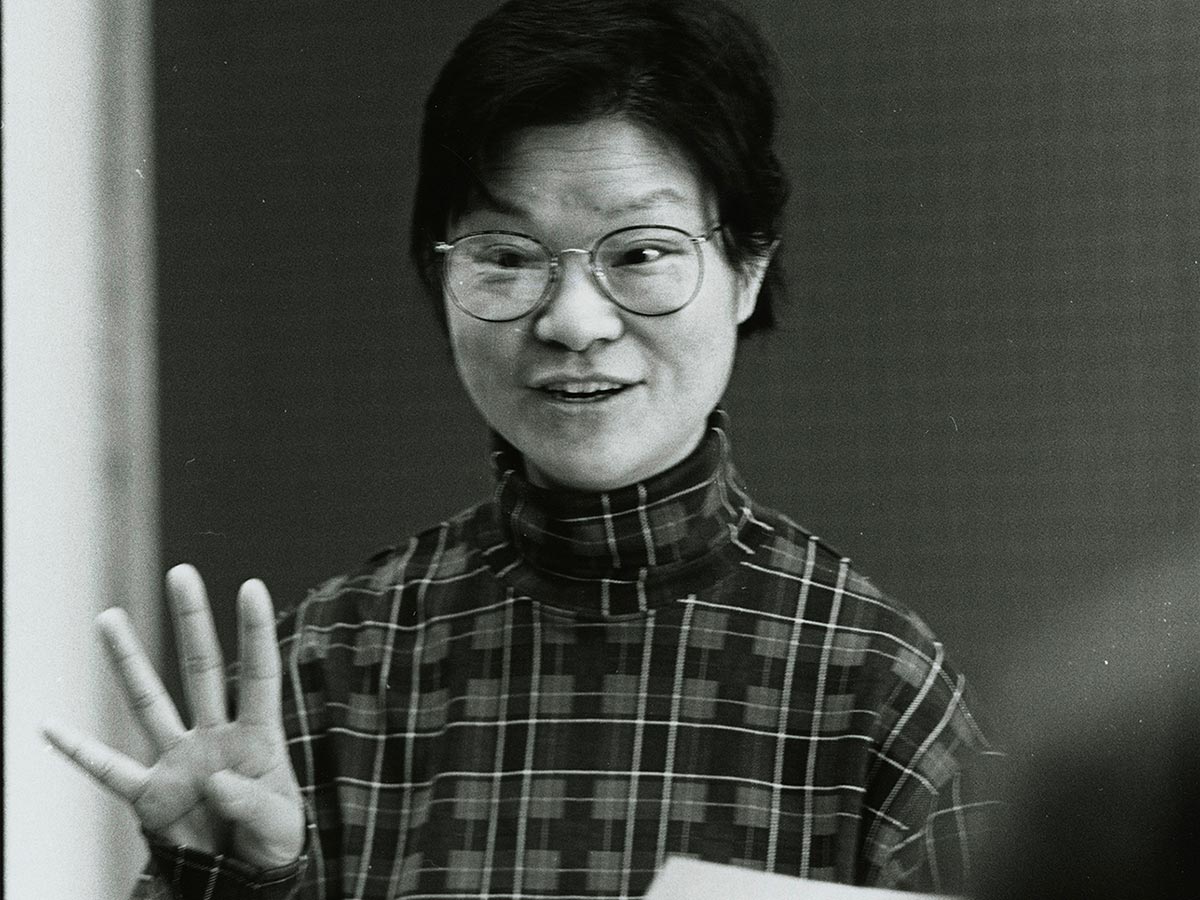

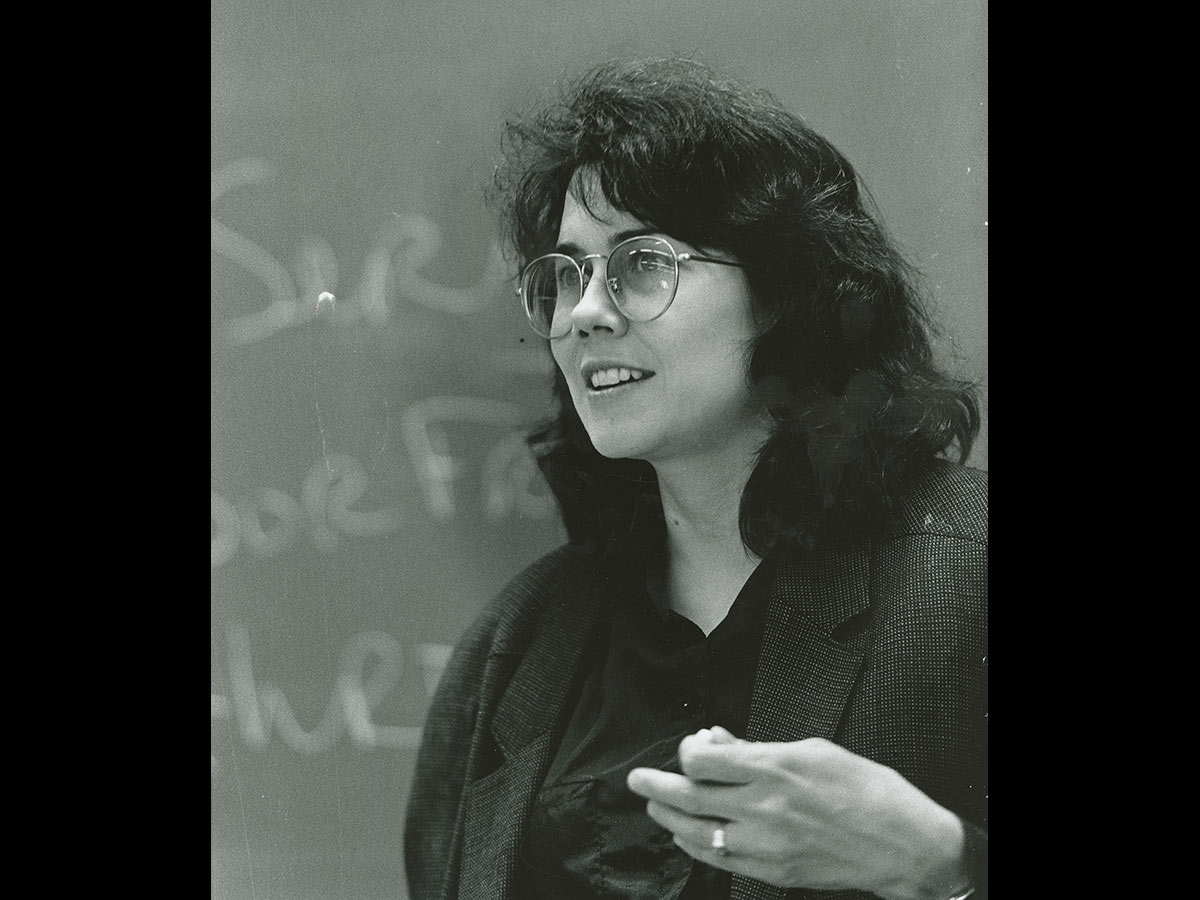

Myra Okazaki Smith

Psychology

1974–2000

Lynn Staley

English, Medieval and Renaissance Studies

1974–

Marilyn Thie

Philosophy and Religion, Women’s Studies

1974–2011

We jokingly called it “The Year of the Woman,” but knew it immediately and most seriously as a year to celebrate. A year when women in numbers joined men as teachers and students in the enterprise that is higher education and in this place that is Colgate.

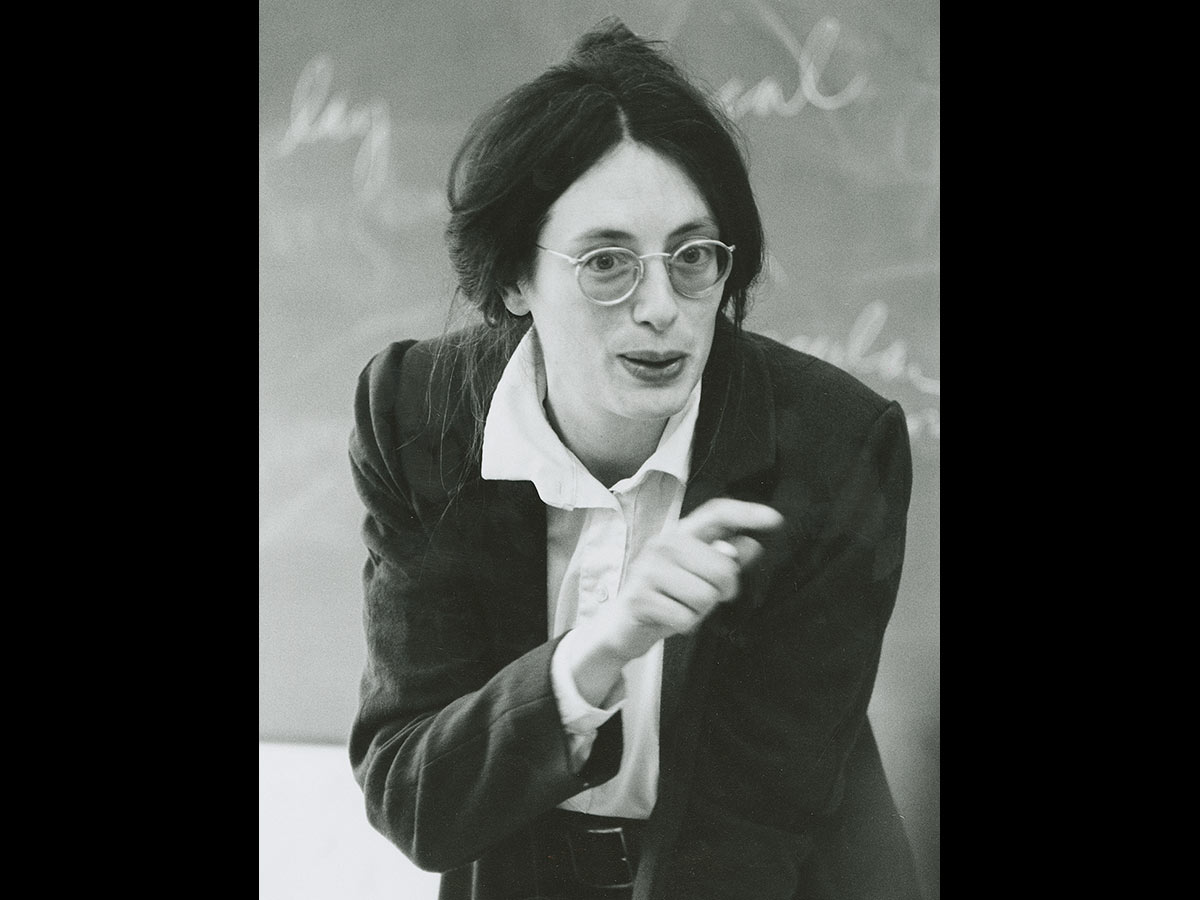

Faculty women of invention

It was, nevertheless, a hard slog, because in many fields these women were inventing almost everything as they went along. Inventing how to be a teacher without pipe or wife. Sometimes inventing how to reconstruct a classroom. At a symposium at Colgate in April of 2018, one of the speakers, Marilyn Thie’s former student Marianne Janack ’86, who now holds a distinguished chair on the faculty at Hamilton College, spoke of how the very structure of authority changed in Marilyn's classroom, in that circle, sitting next to one’s teacher.

And scholarship and research changed. The literary figures whom I studied in graduate school, the teachers from whom I studied, the novelist and poets about whom I wrote — like Wallace Stevens — were all men. There was nothing that I’d met called women’s studies. Scholarship on figures like the contemporary theologian and philosopher Mary Daly awaited the writing of people like Wanda Warren Berry; figures like the medieval writer Margery Kempe were to move to prominence in works like Lynn Staley’s Margery Kempe’s Dissenting Fictions.

At Colgate, we worked together to get a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to start an introductory course in women’s studies, a course then not-fortuitously called Women in the Anglo-American Tradition.

I have talked with my faculty colleagues, and practically to a person — across fields, and for almost a quarter of a century — they have each said the same thing: “What I was to teach and write about was not taught to me; there was no canonical backdrop.”

For example, Ulla Grapard, who came to Colgate in 1985, and who with a cohort of economists around the country, indeed around the world, together reconceived the study of women in economics; and Kay Johnston in educational studies, who joined figures like American feminist, ethicist, and psychologist Carol Gilligan, in unpacking what had been thought of as universal ethical ideals, and showing how gender shaped a field’s perspectives.

We were, at Colgate, certainly not working alone; we were part of a shift in teaching and scholarship, and indeed in institutional service, that left us sometimes but a few steps ahead of our students, in an enterprise that could be as terrifying as it was exhilarating.

Below, we some of the women at Colgate who reimagined their work and this college, and who did so with one another, and with their peers.

Alice Nakhimovsky

Jewish Studies, Russian and Eurasian Studies

1975–

Marietta Cheng

Music

1976–

Deborah Knuth Klenck

English

1978–

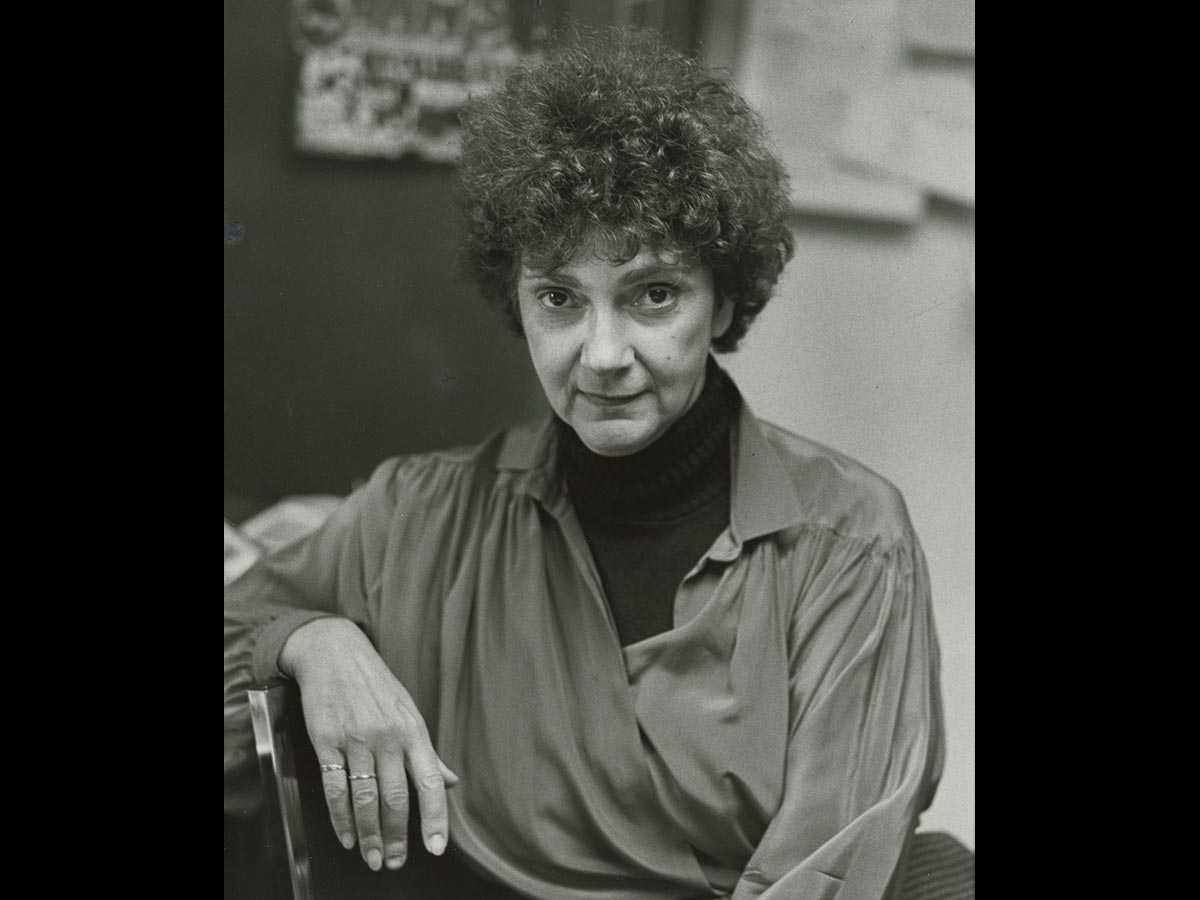

Jo Anne Pagano (dec. 2018)

Educational Studies

1981–2011

Lynn Schwarzer

Art and Art History, Film and Media Studies

1981–

Gloria Bien

East Asian Languages and Literatures

1982–2017

Ann Lane (dec. 2013)

History and Women's Studies

1983–1990

Ellen Percy Kraly

Geography, Environmental Studies

1984–

Lourdes Rojas-Paiewonsky

Romance Languages and Literatures, Africana and Latin American Studies

1984–

Ulla Grapard

Economics and women’s studies

1985–2015

Mary Moran

Anthropology, Africana and Latin American Studies

1985–

Margaret Flanders Darby

Writing and Rhetoric

1986–2015

D. Kay Johnston

Educational Studies

1986–2014

Laura Klugherz

Music, Africana and Latin American Studies

1988–

Carol Ann Lorenz

Native American Studies

1989–

Maureen Hays-Mitchell

Geography

1991–

Nancy Ries

Anthropology, Peace and Conflict Studies

1993–

Georgia Frank

Religion

1994–

Regina Conti

Psychology

1995–

Karen Harpp

Geology, Peace and Conflict Studies

1998–

Damhnait McHugh

Biology

1998–

Nina Moore

Political Science

1998–

Carolyn Hsu

Sociology

2000–

Meika Loe

Sociology, Women’s Studies

2002–

Jennifer Brice

English

2003–

Kezia Page

English, Africana and Latin American Studies

2003–

Women of the administration

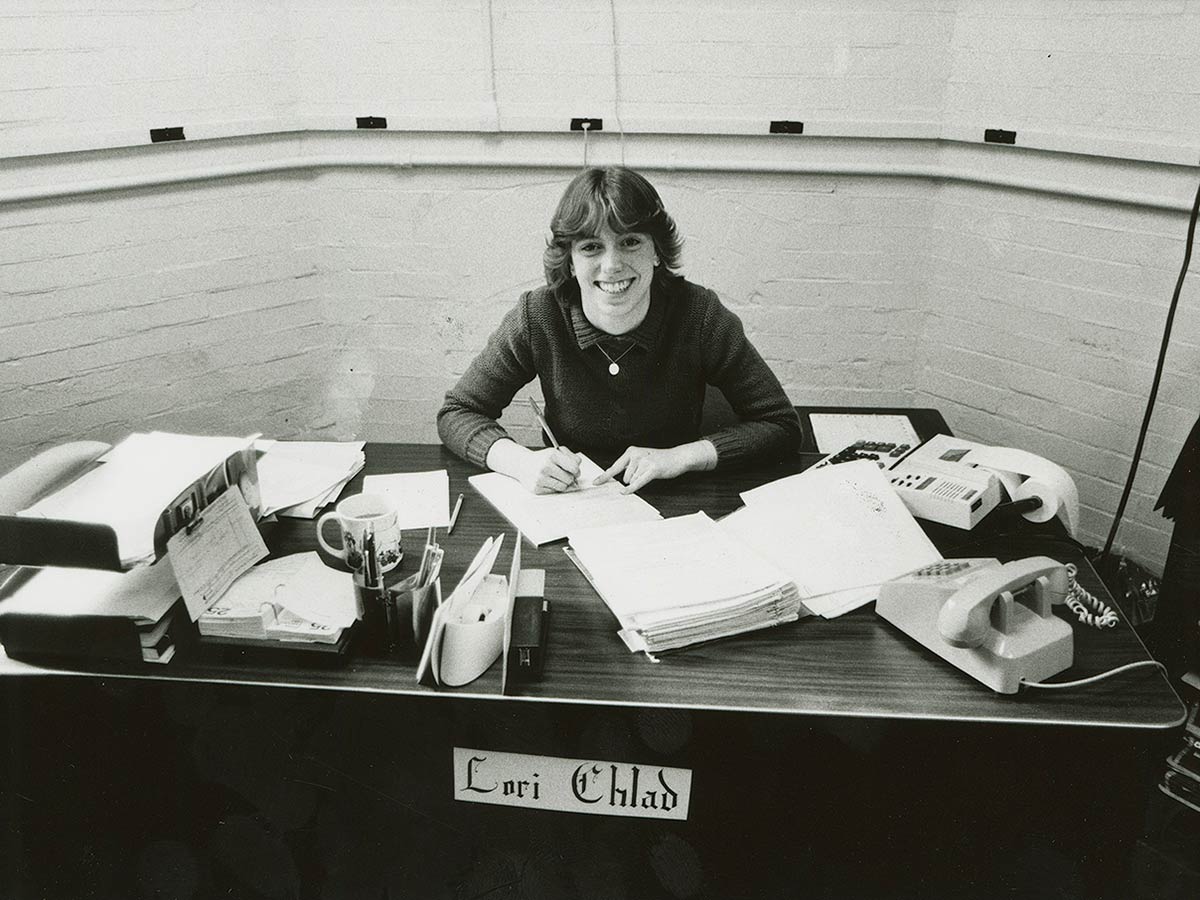

As well as teaching, women were occupying other roles that had not been conceived of in our image. Here one thinks of women on the administrative staff who also have been leaders in many ways, such as Dr. Merrill Miller, director of student health services, who when asked how she could treat football players twice her size, said she’d ask them to sit down; Trish St. Leger, vice provost for administration and planning; RuthAnn Loveless, former vice president of alumni affairs; and Lori Chlad, associate vice president for human resources; Patty Caprio, senior philanthropic advisor; and, the institution’s unsung historian, Helen Payne, assistant to the provost and dean of the faculty, who retired in 2018 after 40 years at Colgate, and Claudia Caraher, assistant to the president, retiring in our Bicentennial year after three-and-a-half decades at the University.

I should add that in my first years at Colgate there were three women who in a sea of men in office ran much of the college’s business under the radar. Peg Fenner, along with Arlene Loop, and Marge Loop. Their Colgate story has yet to be told.

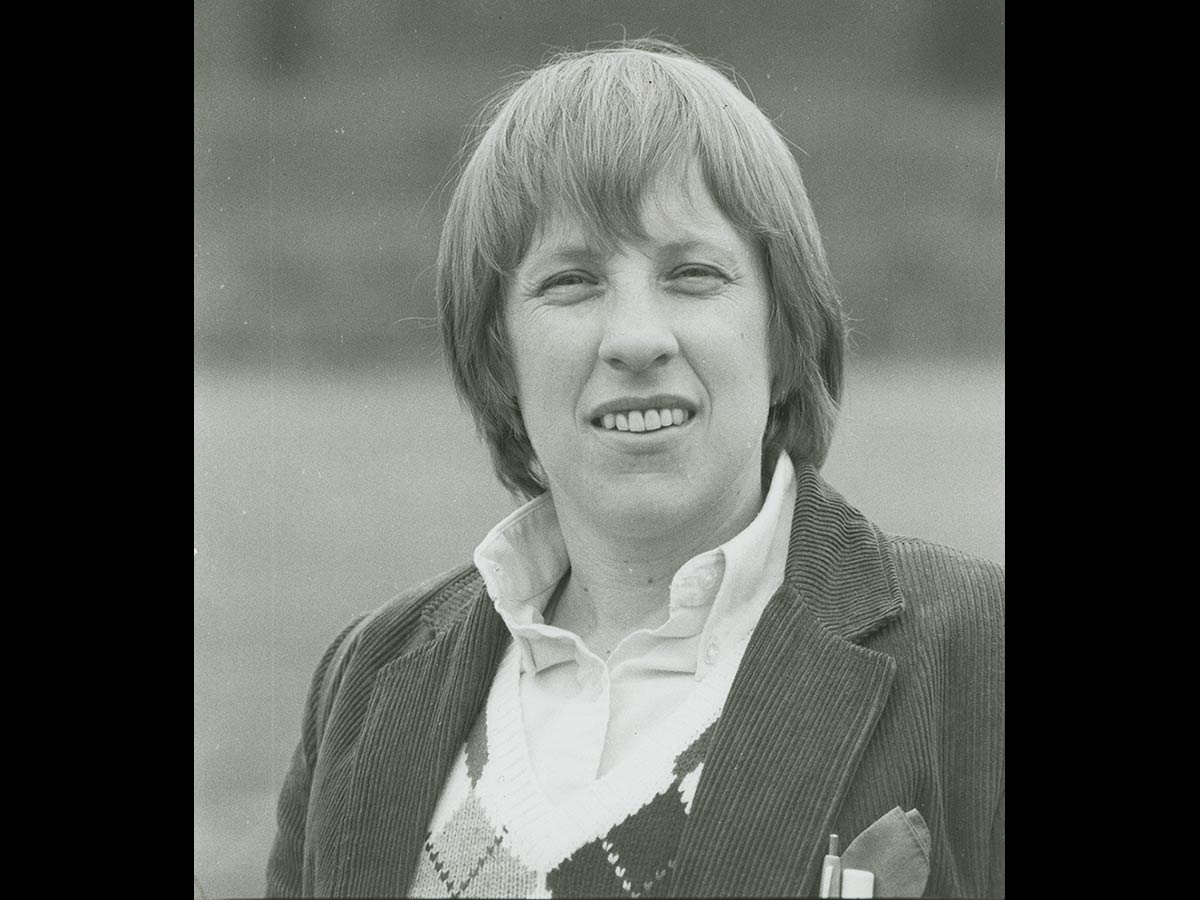

And of course the women on the athletics staff, including Janet Little, who led in athletics at a time before the influence of Title IX, when men and women experienced athletic play in completely different ways.

Merrill Miller

University physician

1981–

Trish St. Leger

Vice Provost

1998–

RuthAnn Loveless MA’72

Retired as VP, Alumni Affairs

1984–2011

Lori Chlad

Associate VP, Human Resources

1980–

Patricia Caprio

Senior philanthropic advisor

1972–

Helen Payne

Assistant to the provost and dean of the faculty

1973–2018

Claudia Caraher

Assistant to the president

1984–2019

Peg Fenner

Administrative secretary, Office of the Dean of Faculty, athletics

1959–1985

Arlene Loop

1966–1987

Retired as administrative secretary, Office of the Dean of the Faculty

Marge Loop

1965–1981

Retired as associate dean of student activities

Janet Little

Recreational sports and physical education

1977–2012

All these women worked together, talked together, and changed their fields and their institution’s priorities. They taught one another and, it’s fair to say, bent the linear, hierarchical model.

And they had help. There was, even when women first came to Colgate, an extraordinary camaraderie on this faculty. And a sense that the faculty were always institutional stakeholders at Colgate, with many male colleagues who fully joined the enterprise for equal education. And institutional leaders who did the same:

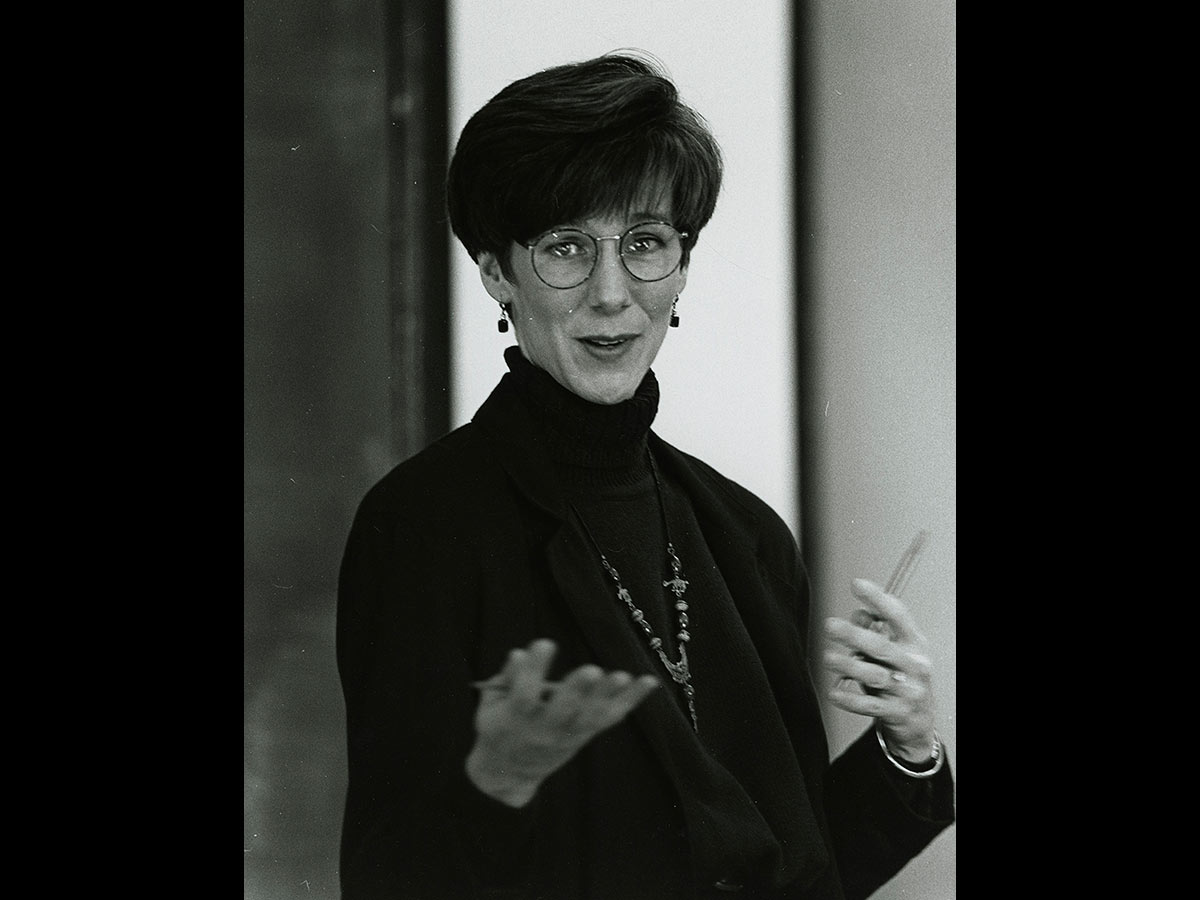

Rebecca Chopp

President

2002–2009

Jill Harsin

Interim president, 2015–16; history

1982–

Constance Harsh

Interim provost and dean of the faculty, 2015–17; English

1988–

Vicky Chun ’91, MA’94

Vice president and director of athletics

2013–2018

Tracey Hucks ’87, MA’90

Provost and dean of the faculty

2017–

Unlike many colleges and universities, Colgate did not support a separate-but-equal enterprise. It did not build another women’s college, as did institutions like our near neighbor, Hamilton College, which began a short-lived Kirkland College in 1968.

Colgate faculty and students at the 2017 Women's March

A student interviewing me in 1998, asked whether the generation of women who came to Colgate in the 1970s was influenced by the feminist Betty Friedan. I answered no, that Friedan spoke to an earlier generation of women, caught up in a post-war and institutionalized celebration of domesticity; that the women who studied and taught here in 1974 were ready for a more feisty reality.

But of course, history does not simply move in a linear, ascending direction. Students in 1998 were not feisty, they saw themselves in a bubble, protected from external news and world conflict.

Women students today

Where are women students today, 20 years later?

Without doubt, there's much to be done before we can answer that question. Or the questions Virginia Woolf poses when she asks whether women’s education should follow a male model.

But there is also much to be grateful for, beginning with a celebration of the camaraderie that has accompanied women's work, elsewhere and especially at Colgate. A camaraderie I knew in my early years here, and that I know now, and that I see in others around me.

Work that echoes the narrative voice in Toni Morrison's 1988 novel Beloved, in which two women, “a slave and a barefoot white woman,” move together to bring a child into a frightening world: “The water sucked and swallowed itself beneath them. There was nothing to disturb them at their work. So they did it appropriately and well.”

—Jane Lagoudis Pinchin H’18 joined the English department in 1969 and went on to serve in most of the significant positions in the academic administration, including provost and dean of the faculty and vice president for academic advancement, as well as interim university president in 2001–2002. Her many accomplishments include leading two academic divisions, University Studies and Arts and Humanities; founding the Manchester Study Group; overseeing a revision of the Liberal Arts Core Curriculum; and working to establish the Women’s Studies Program, extended study and linked-course programs, Upstate Institute, and Max A. Shacknai Center for Outreach, Volunteerism, and Education (COVE). In addition, she has been an active volunteer in several capacities, including the Community Memorial Hospital Board of Directors and the Bowdoin College Board of Trustees. Colgate’s Alumni Corporation created its Humanitarian Award in her honor in 2003. She continues to serve Colgate as a member of the Bicentennial Committee.

Notes & Sources

Images in order of appearance

- Images in order of appearance

- Freshman mixer: 1965 Salmagundi

- Hugh Pinchin: courtesy of Jane Pinchin

- Wanda Warren Berry: Colgate Office of Communications

- Elizabeth Brackett: Colgate Office of Communications

- Bleser: Office of Communications records, A1009, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- D. Kay Johnston: Colgate Scene website

- Bufwack: Biographical file for Mary Bufwack, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Maurer: Biographical file for Margaret Maurer, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Olcott: Colgate Office of Communications; Photo by Phil Humnicky

- Smith: Biographical file for Myra Okazaki Smith, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Staley: Biographical file for Lynn Staley, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Thie: Biographical file for Marilyn Thie, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Slater: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Bleser: Office of Communications records, A1009, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Nakhimovsky: Colgate University website

- Cheng: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Klenck: Colgate University Website

- Pagano: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Schwarzer: Colgate Office of Communications

- Bien, University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Ann Lane: Biographical file, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Kraly: Biographical file for Ellen Kraly, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Rojas-Paiewonsky: Office of Communications

- Grapard: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Moran: Colgate Office of Communications

- Darby: Colgate Office of Communications

- Klugherz: courtesy of Laura Klugherz

- CarolAnn Lorenz: Colgate Native American Studies Program

- Hays-Mitchell: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Ries: Colgate University Website

- Frank: Colgate Office of Communications

- Conti: Colgate University Website

- Harpp: Colgate Office of Communications

- McHugh: Colgate Office of Communications

- Moore: Colgate Office of Communications

- Hsu: Colgate University Website

- Meika Loe: Colgate Office of Communications

- Brice: Colgate University Website

- Page: Colgate Office of Communications

- Miller: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- St. Leger: Colgate Office of Communications

- Loveless: Colgate Office of Communications

- Chlad: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Caprio: Biographical file for Patricia Caprio, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Payne: Colgate Office of Communications

- Caraher: Colgate Office of Communications

- Fenner: University photograph collection, A0999, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- A. Loop: Courtesy of Jack Loop

- M. Loop: Courtesy of Jack Loop

- Little: Biographical file for Janet Little, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Chopp: Colgate Office of Communications

- Harsin: Biographical file for Jill Harsin, Colgate Special Collections and University Archives

- Harsh: Colgate Office of Communications

- Chun: Colgate Office of Communications

- Hucks: Colgate Office of Communications

- Women’s march: courtesy of Jane Pinchin