Colgate’s campus is situated on the ancestral lands of the Oneida Nation, one of the original nations of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois people. In observance of its Bicentennial, the University’s Native American Studies Program commissioned a historian to investigate how these lands came to be in its possession. Laurence Hauptman, SUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus, researched and unpacked the complex account in a detailed report and a Bicentennial lecture on campus.

Oneida Country

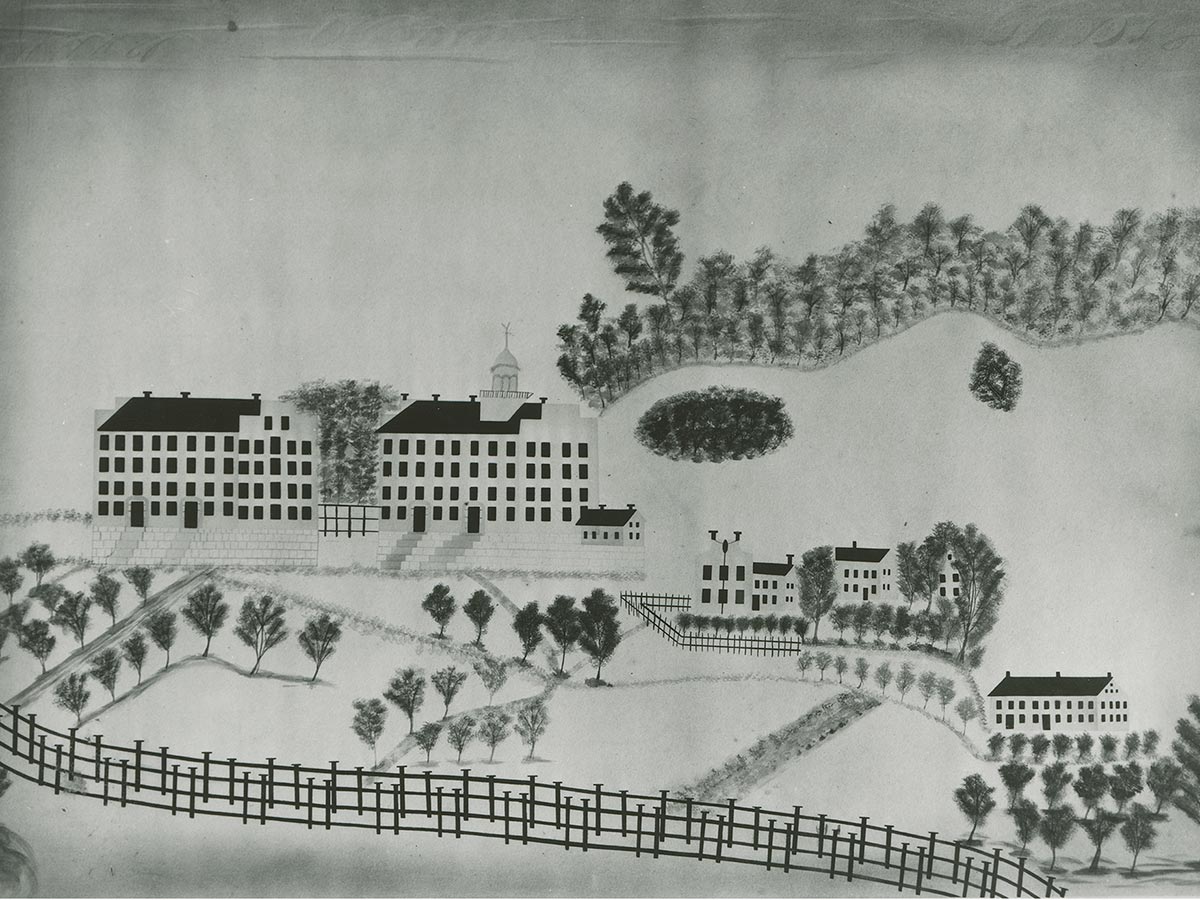

The school that would become Colgate University, the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution, was one of the 180 colleges founded on the American frontier between the end of the American Revolution and the Civil War.1

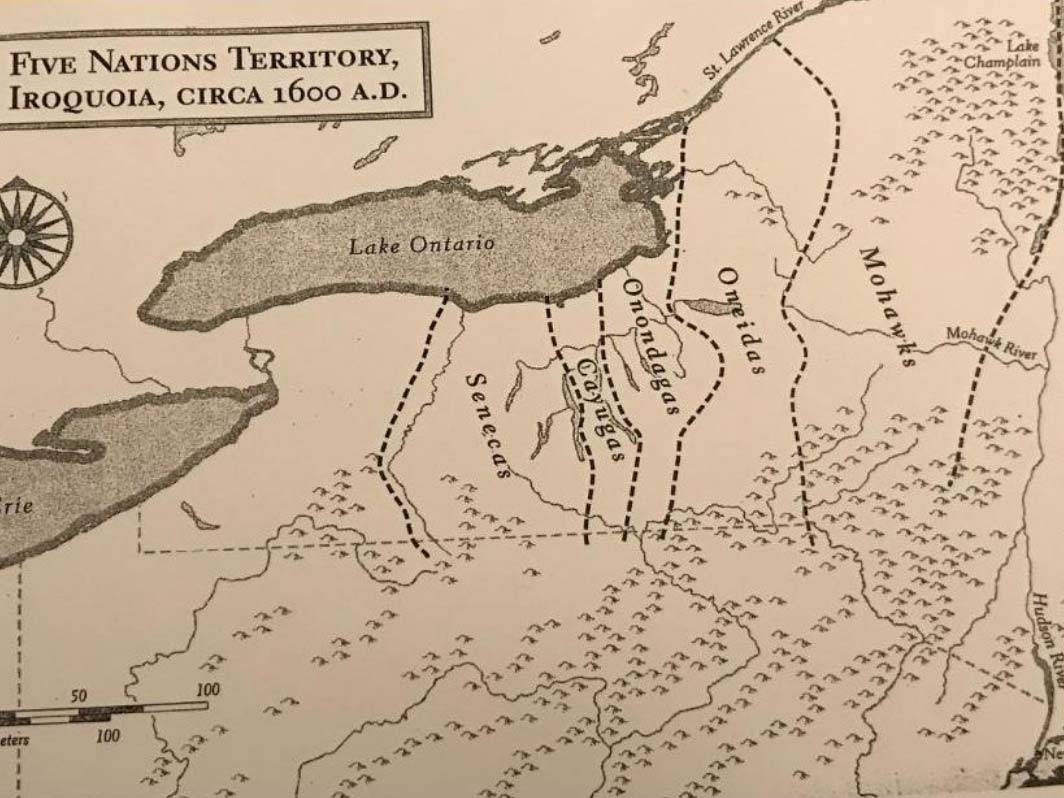

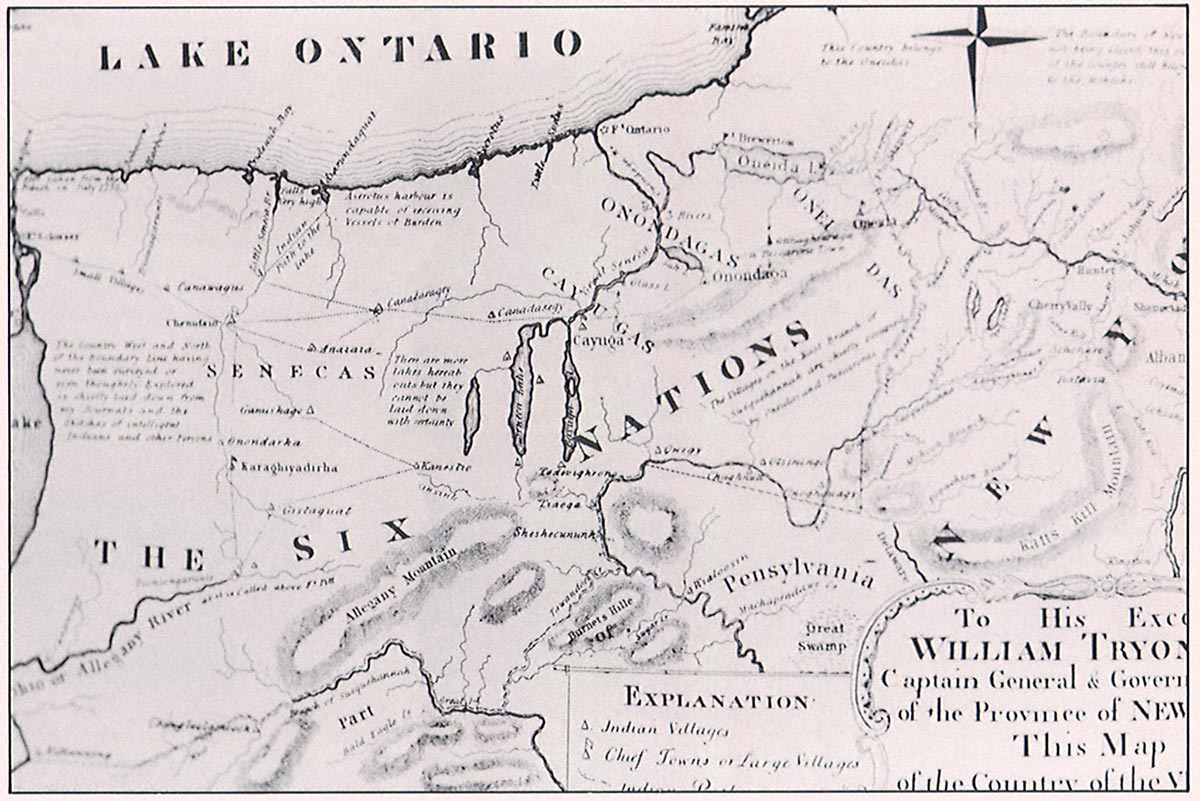

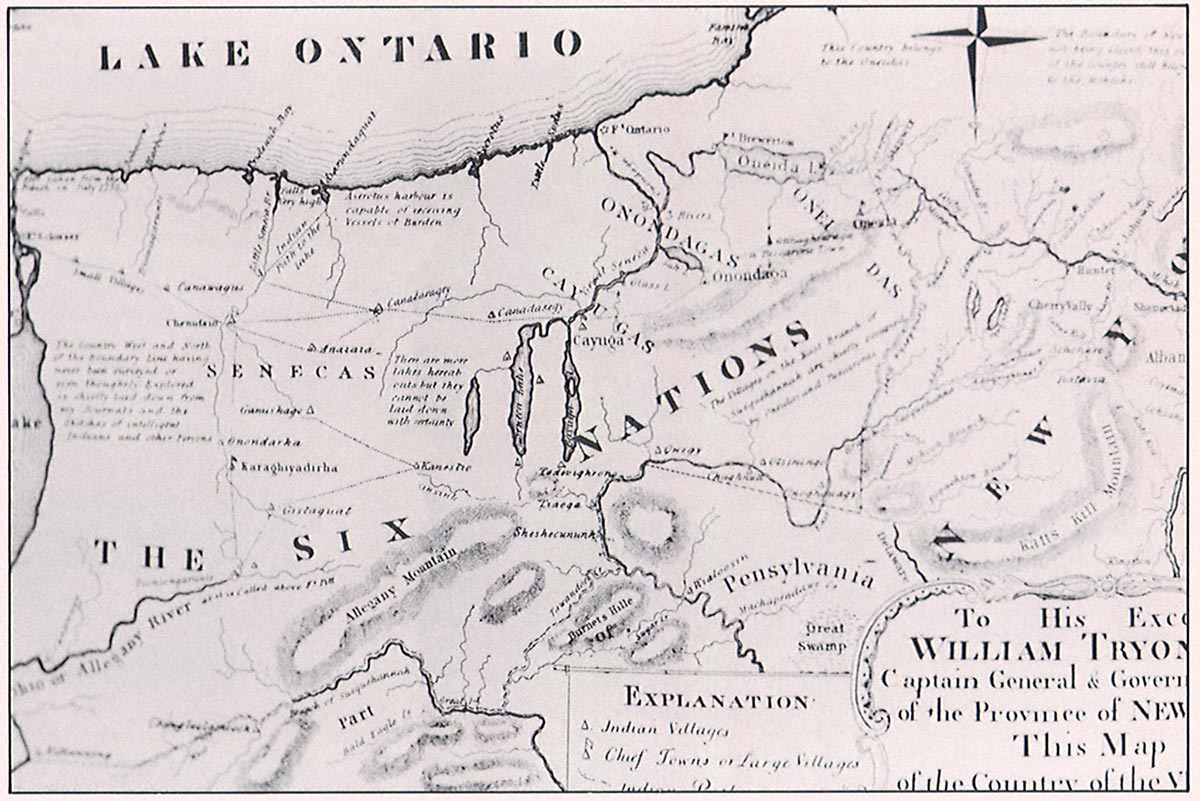

1771 Map of the Six Nations

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Oneida people — one of the original tribes of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Nation — and their ancestors had lived in the region for millenia. The Oneidas, or “People of the Standing Stone,” called Hamilton Da-nde-no-sa, or “round stone dwelling.” They “believed that they were protected by the Creator’s gift of a boulder that appeared magically every time they moved their villages.”2

The region was rich with resources, and the Oneidas lived in an area covering more than six million acres of fertile lands extending from the St. Lawrence River to today’s Pennsylvania border. They were semi-sedentary people who raised the “Three Sisters” crops of maize, beans, and squash using a form of slash-and-burn horticulture. In addition, they gathered wild plants, berries, and nuts; hunted deer, fowl, and other game, and fished the abundant lakes and rivers,3 employing a temporary campsite in the vicinity of Colgate’s campus off and on into the early 1600s, according to archaeology conducted by professor Jordan Kerber (sociology and anthropology, Native American studies) and his Colgate student researchers.4

Dispossession

Given the area’s strategic location, the region’s land was coveted and contested by colonial, state, and federal officials; military officers; land speculators; and turnpike and canal developers.5 The Oneidas were drawn not only into negotiations for land cessions,6 but also wars.7

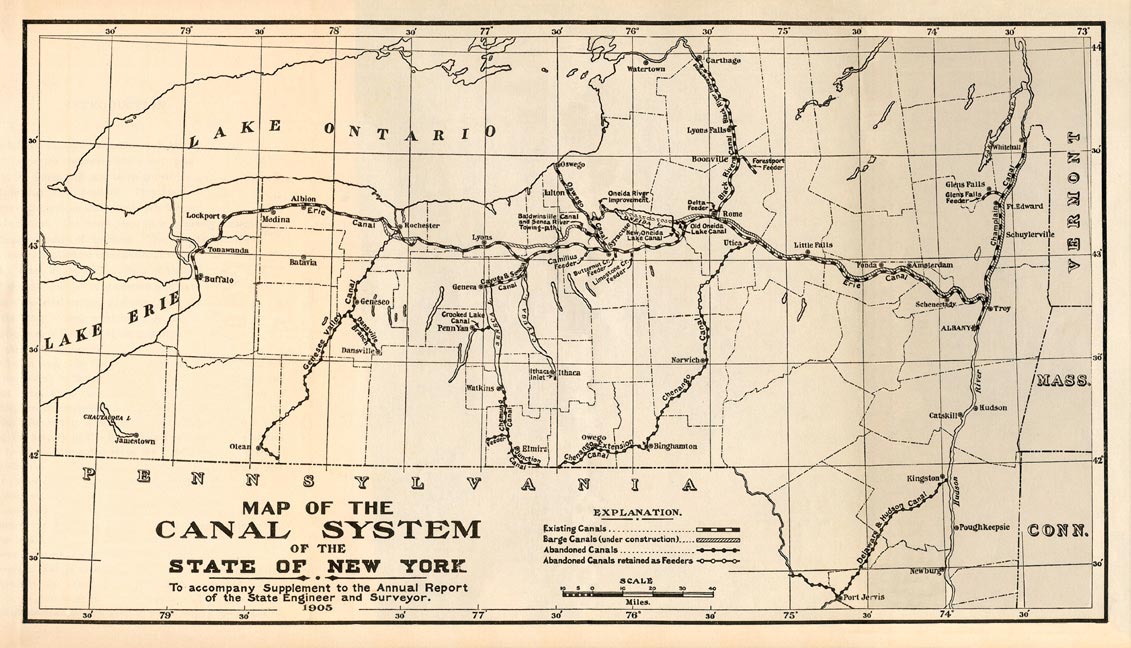

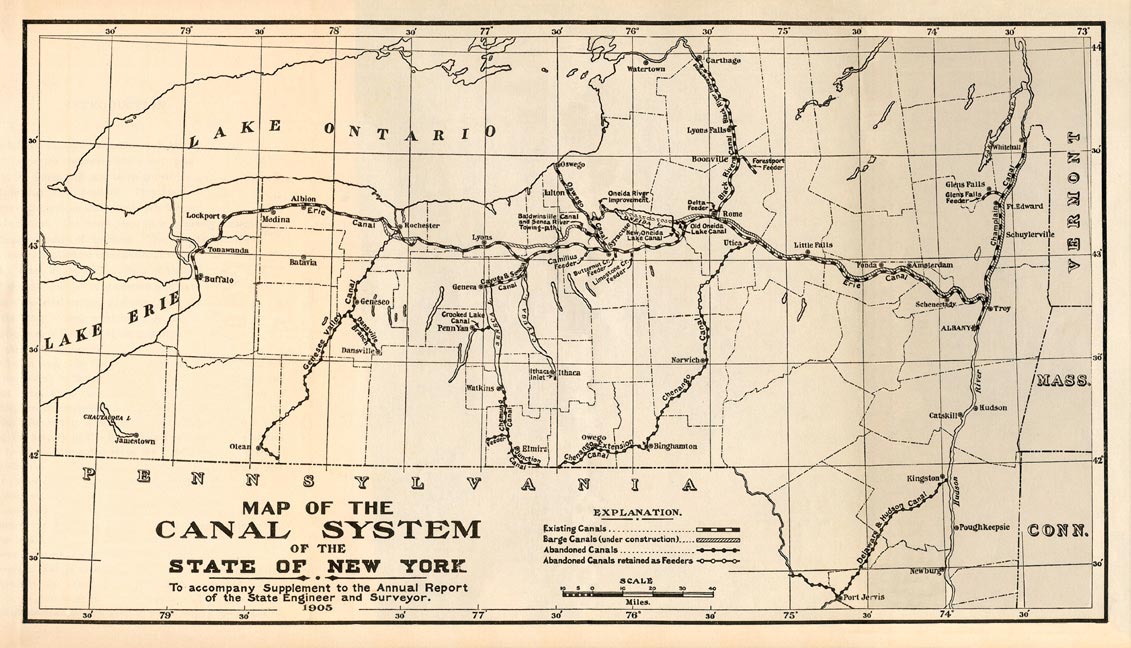

New York State’s vast canal system, 1906. Many canals, all built before 1840, cross historic Oneida Territory.

Of note, after the Revolutionary War, prominent New York State families conspired to gain control of these resource-rich lands.8 For example, politician Philip Schuyler, the father-in-law of U.S. founding father Alexander Hamilton — for whom Colgate’s hometown would later be named — was “the individual most responsible for the New York State-Oneida Treaty of September 12, 1795, held at Albany that dispossessed the Oneidas of approximately 250,000 acres.”9

Schuyler and other powerful New York families such as the Livingstons “‘tripped over their own feet’ competing with each other in their lust for Indian lands. Each saw that if New York State was opened up by the improvement of navigable waterways, the building of canals, and the construction of roads and turnpikes, the result would be a sizable increase of white population. Economic growth would spur land sales (as well as land prices), benefiting themselves and their political cronies.”10

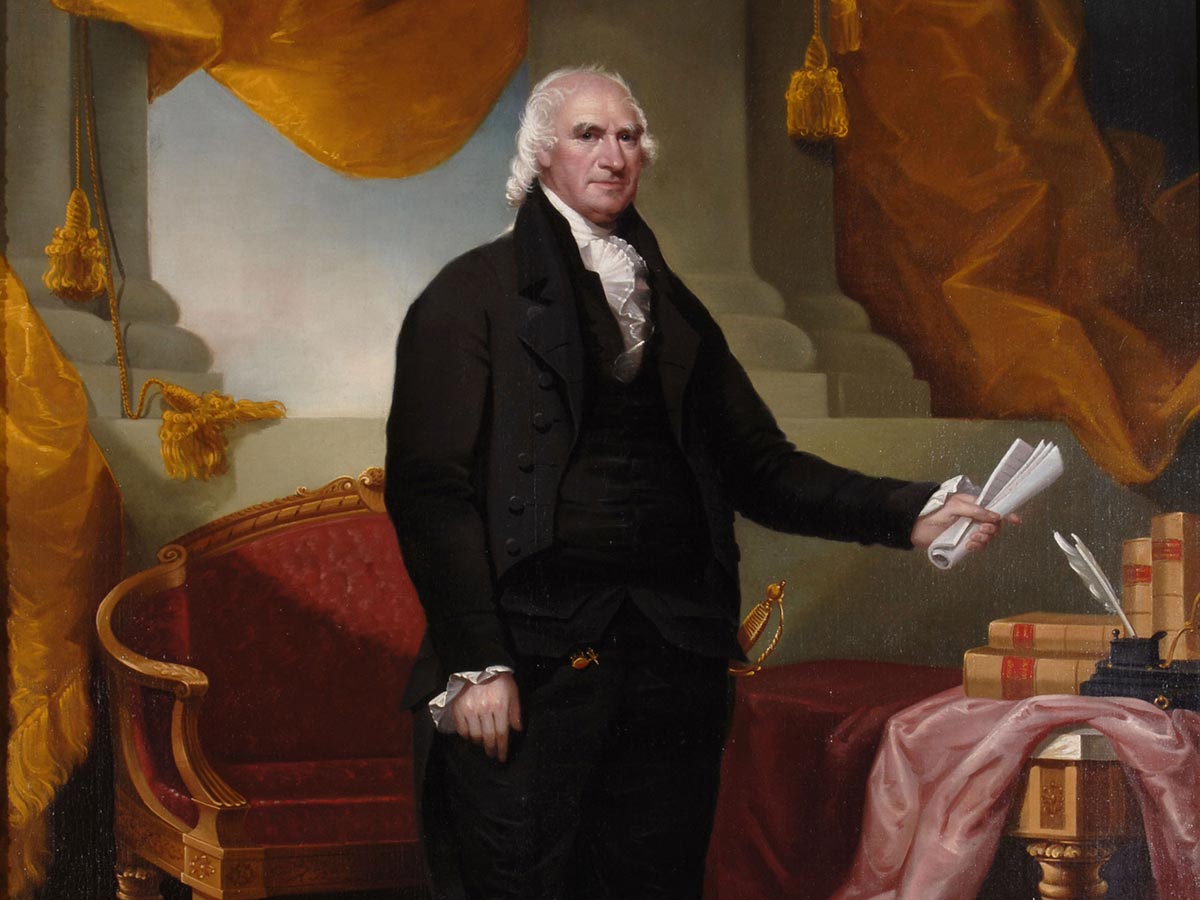

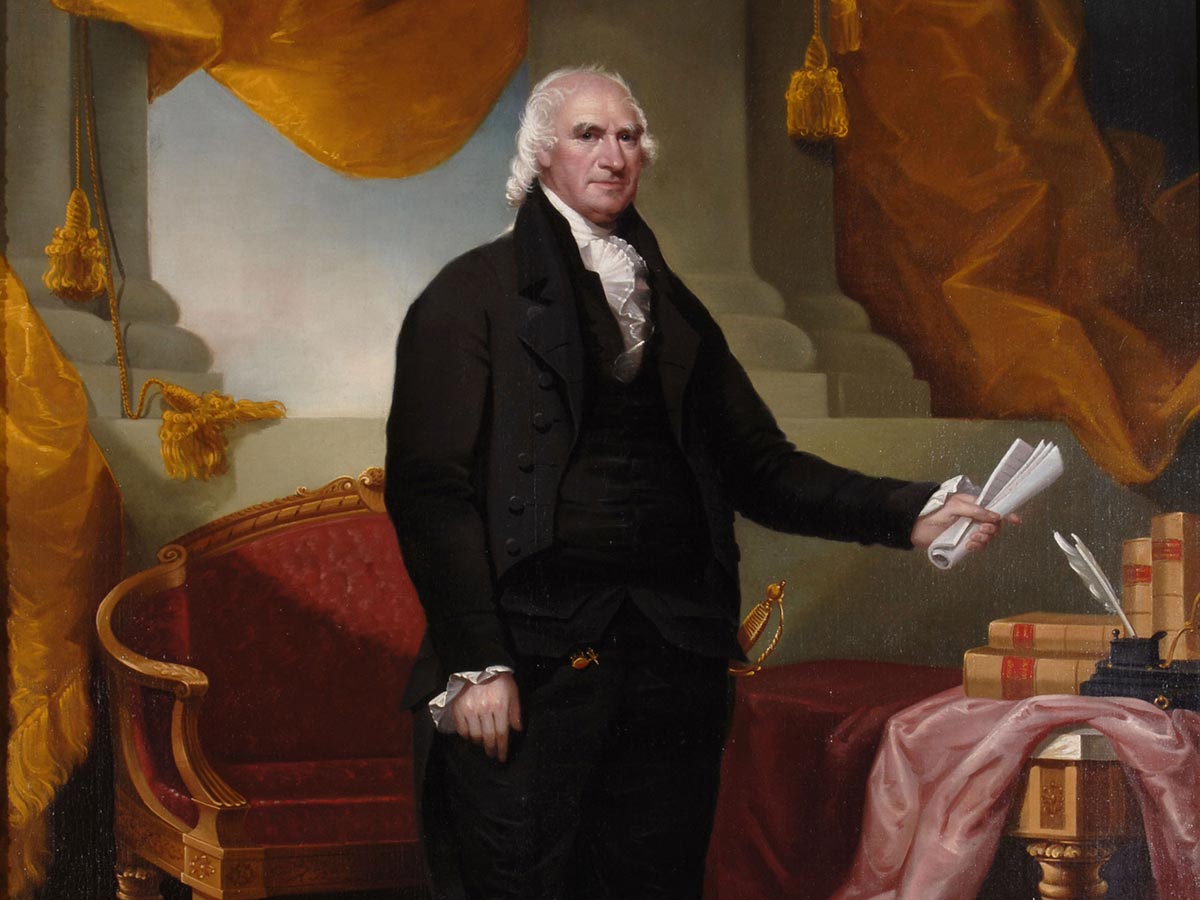

Governor George Clinton, seven-time governor of New York State and later vice president of the United States

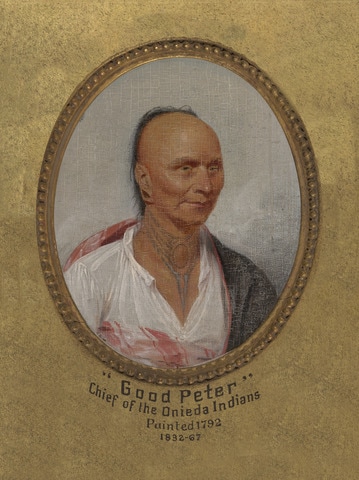

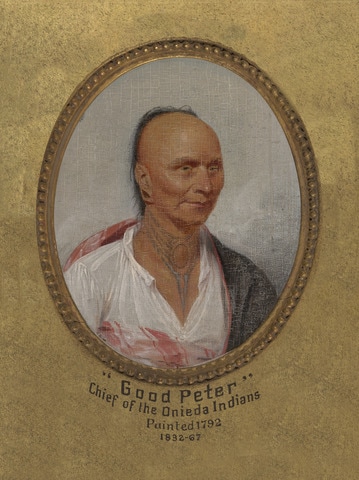

Governor George Clinton had made promises to the Oneidas: that they and their lands would be respected, and that he would enforce state constitutional law forbidding Indian land sales to individuals without legislative permission. But, he was soon breaking them. With the Treaty of Fort Schuyler in 1788, New York State acquired 5 million acres for “safekeeping” through what Hauptman calls “a late–18th-century version of a Mafia protection racket.” Oneida Chief Good Peter “and his supporters were caught — on one hand fearing avaricious land speculators colluding with some of his people; and on the other, he feared the likelihood that the state government would not protect them and allow numerous non-Indian settlers to pour in and trespass on Oneida territory” — so they reluctantly conceded to Clinton and signed the “accord.”11

Despite Governor Clinton’s questionable actions in executing that treaty, U.S. Federal courts in more recent days have decided that it was legally binding.12

Good Peter, Oneida Chief (ca. 1717–1793)

By the early 1790s, acts of the state legislature provided for the survey and sale of the lands ‘acquired’ at the Fort Schuyler Treaty. William Stephens Smith — son-in-law of U.S. founding father John Adams, then vice president of the United States — purchased six of these townships. Soon after, Smith sold parcels within one township to Dominick Lynch of Utica, including a 123-acre parcel south of what would become the village of Hamilton. Lynch, in turn, sold that farm to Samuel Payne.

Payne’s Farm

With that purchase, Payne and his wife, Betsey, became the first non-Indian settlers in the area, in 1794.

Arriving the next year, Payne’s brother Elisha purchased a nearby lot, founding what was first called in 1796 “Payne’s Settlement,” now the Village of Hamilton.13 Although Samuel served briefly as a judge and a New York State assemblyman [1804–1806], he was mainly a merchant and worked his lot as a farmer.

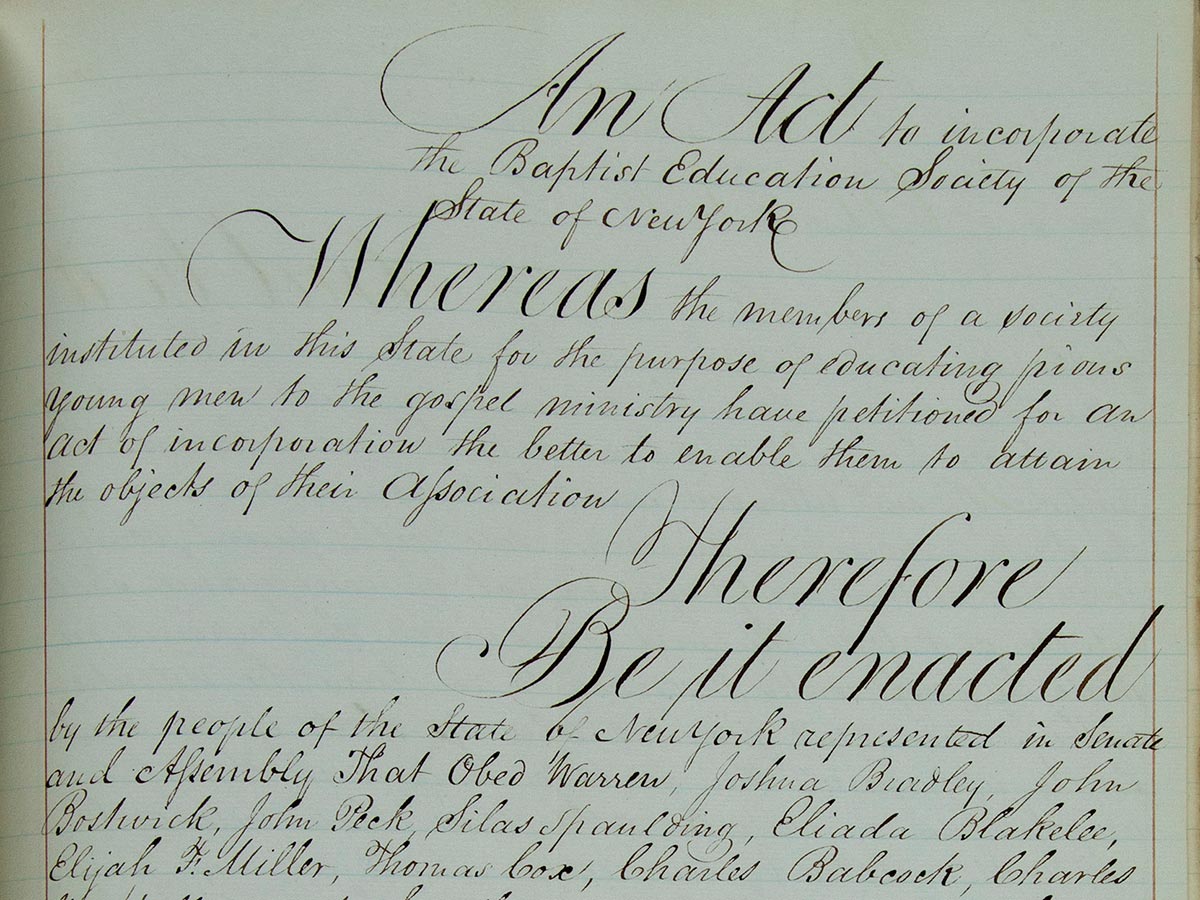

Samuel and Elisha became active members of the Madison Baptist Association, founders of the First Baptist Church in Hamilton (where Samuel served as a deacon), and joined 11 others in founding the Baptist Education Society of the State of New York.14

Monument on the Academic Quadrangle commemorates Samuel Payne’s felling of the first tree on the land that would become Colgate University’s campus.

In 1826, Payne sold his land to the society for half its value — $2,000 — to serve as the campus for the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution, which would become Colgate University. Not long thereafter, the society constructed its first building, the Western Edifice, of Chenango sandstone quarried from the hill.15 (Chenango, the name of the valley below, is an Iroquois word meaning “bull thistle,” a medicinal plant used by Oneidas to treat upset stomach.16)

The Baptists and the Oneidas

The archaeological evidence suggests that the Oneidas did not permanently reside in the Town of Hamilton, including Colgate’s campus. Native Americans employed a temporary campsite in the vicinity of Hamilton off and on for thousands of years into the 1600s, but, as yet, “No evidence of a permanent village site, no palisaded structure, and no longhouse residence have ever been found.”17 Archaeological testing on the Colgate campus in 2004 found no evidence of prehistoric or historic materials before Samuel Payne set up his farm.18

Although eventual possession was made possible by the state treaty with the Oneidas at Fort Schuyler, none of the original 13 founders of the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution had participated in the councils in 1788, nor in other treaties with the Oneidas.19

Although they protested to Washington against the forcible removal of the Oneidas from New York, local Baptists, including those at the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution, later supported efforts to cooperate with federal authorities in pushing Indian removal policies.

In its earliest days, the institution’s student body included Native Americans. In 1826, seven young men from the Carey Mission in Michigan were enrolled; of Odawa, Ojibwe, Miami, Potawatomi ancestry and between 13 and 19 years of age, they all attended for at least two years.20

Colgate University’s campus is part of the Oneida territory that

“allowed New York ... to become the Empire State. To Albany politicians and to the emerging capitalist class in Alexander Hamilton’s America, the lands in Iroquoia were essential for economic development as well as for national security ... They viewed the Oneidas’ six million acres as vital for the building of a transportation network that would further land sales and populate New York’s frontier. Acquiring these lands would ensure New York’s economic future — its agricultural potential, its rich forests and fisheries, and its salt marshes and mines. The sale of Hodinöhsö:ni´ [Haudenosaunee] lands provided the very capital for future investment filling the state coffers and lining the pockets of individual entrepreneurs.”21

In contrast, over time, the Oneidas’ population dwindled precipitously as they lost their lands. By 1890 — the year that Colgate University got its name — fewer than 300 Oneidas lived in New York, in two small communities on fewer than 1,000 acres approximately 20 miles north of the campus. “By the turn of the 20th century, the last unallotted Oneida lands, the so-called ‘32 Acres’ or ‘Windfall,’ along West Road in the Town of Lenox, the homestead of Mary and Margaret Scanandoah and their extended families, was all that was left of the Oneida territory that had been 6 million acres in 1784. In 1909, the Oneidas there were evicted illegally from this property. In an eleven-year legal struggle in federal courts, the Scanandoahs were to win back this 32-acre parcel and set in motion the modern Iroquois land claims movement.”22

Studying Local Legacies

Students in Professor Jordan Kerber’s Fall 2012 Field Methods and Interpretation in Archaeology course excavate Oneida artifacts at the Brunk site, an ancient Oneida village in northern Madison County.

Students in Professor Jordan Kerber’s Fall 2012 Field Methods and Interpretation in Archaeology course sort and catalog items they found at the Brunk site, an ancient Oneida village in northern Madison County. The students wrote reports interpreting the results in an attempt to reconstruct the activities that may have occurred at the site.

Colgate’s Native American Studies Program draws on a wide range of disciplines to examine Native American issues in great depth to provide a transformative and revealing study of the contributions of America’s original peoples.

Students in the program, which offers both a major and minor, develop a foundation of knowledge that can be applied to professional work or continued study in inter-American relations, Latin American studies, anthropology, archaeology, history, government services, art history, museum studies, religion, and more.

Established in the mid-1900s, Colgate’s Longyear Museum of Anthropology has the most comprehensive collection of Iroquois materials, especially Oneida, in the region. Some of its holdings were excavated by Colgate professors and students. In keeping with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, institutions receiving federal funding must publish an inventory of its Native American holdings so that federally recognized tribes with an affiliation to specific objects — for example, funerary and sacred objects — may request repatriation. Colgate has repatriated several objects to their affiliated tribes, and in other cases, the tribes have allowed the University to retain the objects, as long as they are not displayed.

A resource for Colgate students as well as for the community, the collection is frequently used in academic courses.23

Laurence M. Hauptman

Laurence M. Hauptman is SUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at SUNY New Paltz, where he taught courses on Native American history, New York history, and Civil War history for 40 years. The author, co-author, or co-editor of numerous articles and books on the Haudenosaunee and other Native Americans, he has been honored by the N.Y.S. Board of Regents, Pennsylvania Historical Association, Wisconsin Historical Society, New York Academy of History, N.Y.S. Historical Association, and Mohonk Consultations. Hauptman has testified as an expert witness before committees of both houses of Congress and in the federal courts. He has served as a historical consultant for the Wisconsin Oneidas, the Cayugas, the Mashantucket Pequots, and the Senecas. He is the recipient of the State Archives Lifetime Achievement Award and the Peter Doctor Memorial Indian Scholarship Foundation Award (twice) from the Six Nations for his writings and applied work on behalf of Native Americans in eastern North America. In 2011, the Seneca Nation of Indians bestowed on him the name Haiwadogêsta, meaning “interpreter” or “he straightens or explains the words.”

Notes & Sources

- Laurence M. Hauptman, “How Oneida Lands Became Colgate,” Report to Brian Casey, President, Colgate University, 2018, 8.

- Ibid, 11

- Ibid, 17, 18

- Ibid, 13

- Ibid, 21

- Ibid, 22

- Ibid, 27

- Ibid, 29

- Ibid, 25

- Ibid, 30

- Ibid, 35–36

- Ibid, 39

- Ibid, 49

- Ibid, 11

- Smith, James A., Becoming Colgate, Colgate University Press, 2019

- Hauptman, 12

- Ibid, 13

- Ibid, 13

- Ibid, 40

- Ibid, 58–59

- Ibid, 59–60

- Ibid, 63

- “Local Legacies,” Colgate Scene, Winter 2013.

- Early campus drawing, Colgate University Drawing, Sketch, and Painting collection, A1212

- Iroquoia, ca. 1600, Joseph T. Glatthaar and James Kirby Martin, Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang 2006 OR: Historic Oneida Territory with present-day counties: Christopher Vecsey and William A. Starna, eds., Iroquois Land Claims. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press 1988 OR: 1771 Map of the Six Nations, Pictures Now/Alamy Stock Photo

- New York’s canal system, Noble E. Whitford, History of the Canal System of the State of New York. Albany: Annual Report of the State Engineer and Surveyor, Brandon Printing, 1906. Downloaded from Erie Canal.org

- Governor George Clinton, Painting by Ezra Ames, 1802. Hall of Governors, New York State Capitol, Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons

- Oneida Chief Good Peter (c. 1717–1793), painting by John Trumbull. Yale University Art Gallery. Downloaded and excerpted from Yale University Art Gallery

- Payne kneeling by cut tree

- Samuel Payne monument, Mark DiOrio, Colgate University Office of Communications

- Brunk site excavation, Andrew M. Daddio, Colgate University Office of Communications

- Cleaning Oneida artifacts, Andrew M. Daddio, Colgate University Office of Communications

- Laurence M. Hauptman, courtesy of the author